The United States 4th Circuit Court of Appeals recently ruled in a firearms-related case that will have broad applications in regards to encounters between police officers and citizens lawfully carrying firearms for self-defense.

This article will specifically address the case US v Robinson. For a broader look at police and citizen encounters, I recommend reading our other articles:

- Concealed Carry and Police Encounters

- Three Tiers of Police Citizen Encounters

- Armed Civilians Saving Lives: FBI Report

The ruling in U.S. v. Robinson (2017) specifically addresses the meaning of “armed and dangerous” in the context of the famous U.S. Supreme Court case of Terry v. Ohio (1968).

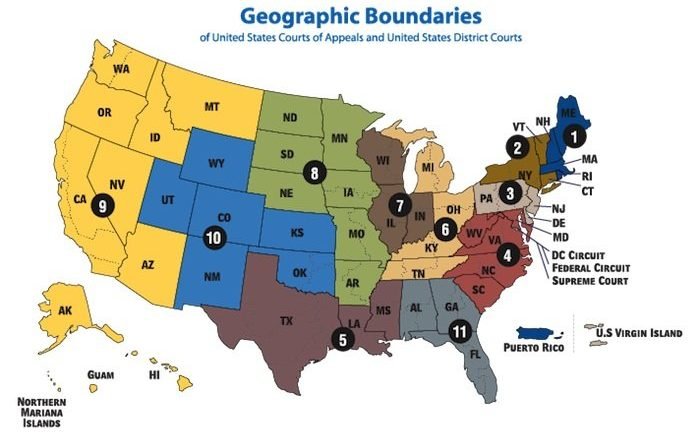

Though many may not see the significance of this latest ruling, there are ample reasons to understand this ruling in regards to concealed or open carry of firearms. Within the U.S. 4th Circuit, at least, a citizen lawfully carrying a firearm openly or concealed may be subject to much more scrutiny by police than they may feel warranted. Considering the U.S. Circuit Courts hold decisions from other Circuits in high regard, this decision may have a broad impact on civilians and police officers across the country. Read on for more details.

EDITOR’S NOTE: Blue Sheepdog strives to keep our readers informed on the latest legal rulings having a direct impact on their daily duties. Our hope is the reader will become informed of possible changes in the law and how they need to proceed in future contacts. However, these posts are presented as informational-only! The Blue Sheepdog Crew are not attorneys, and this post does not constitute legal advice or direction. Officers and readers should consult their Department Legal Advisors, local Prosecutors, or personal attorneys before acting on the legal principles discussed here.

U.S. v. Robinson (2017)

In March of 2014 officers in West Virginia were advised a citizen reported, “a black male in a bluish greenish Toyota Camry load a firearm [and] conceal it in his pocket” while in a convenient store parking lot. The reporting party advised police the vehicle was driven by a white female and had just left the parking lot, with the direction of travel provided. The location of the convenient store is in a noted high crime area, and the convenient store was a known drug dealing location.

EDITOR’S NOTE: West Virginia recognizes citizens’ rights to bear arms, and had a Concealed Carry Statute (61-7-4) in effect at the time of this incident. One of the cruxes of this case is when and if police officers may treat a person as “armed and dangerous” even if they are legally carrying a firearm and abiding by the laws of their State.

Almost immediately officers were dispatched to the area to look for the Camry, and located the vehicle within a very short period of time. Neither occupant was wearing a seatbelt (a primary violation in West Virginia). The officer conducted a traffic stop based upon the observed violation within “two or three minutes” of the original call, and about 7 blocks (3/4 mile) from the convenience store where the witness had observed the black male loading a firearm.

The officer contacted the occupants to obtain identification, but concerned about a possibly armed individual reaching for I.D. the officer ordered the male passenger to exit the vehicle. The backing officer had arrived by that time and engaged the male passenger after opening his door. The backing officer asked the passenger if he any weapons on him. The officer later testified the male did not verbally respond but gave an “oh crap” look on his face.

The officer then ordered the passenger (Robinson) to place his hands on the top of the car and performed a frisk. During the frisk, a loaded pistol was found in one of Robinson’s front pockets. After recovering the firearm, the backing officer recognized Robinson and knew that he was a convicted felon. Robinson was then placed under arrest for illegally possessing a firearm by a felon and was charged in U.S. District Court.

Robinson’s Motion to Suppress

Robinson filed a motion to suppress arguing the officer’s frisk of his person violated his 4th Amendment rights. Robinson conceded the stop was legal, and the officer had a reasonable belief he was “armed”, but the officer did not possess a reasonable belief that he was “dangerous” (a part of the Terry v. Ohio decision in 1968).

The U.S. District Court denied Robinson’s motion, and he pled guilty with the right to appeal. He then filed a timely appeal with the U.S. 4th Circuit Court of Appeals.

EDITOR’S NOTE: The U.S. 4th Circuit encompasses West Virginia, Virginia, Maryland, North Carolina, and South Carolina. As such, this ruling is now legal precedent within the 4th Circuit. Federal Circuit Courts of Appeal frequently cite other Federal Circuit Court rulings when determining a matter before them. Therefore, this ruling could have broad implications across the United States. Currently, this ruling is only legally binding in the 4th Circuit.

Robinson’s Appeal to the 4th Circuit

Robinson’s appealed to the U.S. 4th Circuit using the same arguments about the frisk performed by the officer and arguing the District Court erred in not granting the suppression of the firearm. Despite the appeal, Robinson conceded these four legal points:

- The stop was lawful and based on a traffic violation

- The police had the authority to order him to exit the car

- The anonymous tip was sufficient to allow police to rely on its information

- The police had a reasonable belief he was armed.

In essence, the only issue on appeal was Robinson’s argument “whether the officers could have possessed a reasonable belief that Robinson was ‘dangerous’ in addition to the fact he was armed, to the extent a frisk would be lawful under the 4th Amendment. This was based upon specific wording in Terry v. Ohio about the officer’s reasonable belief the suspects were “armed and dangerous.” Robinson’s argument was there was no reasonable belief he was “dangerous.”

Robinson even supported his argument by stating West Virginia law, which permitted a person to lawfully carry a concealed weapon in public. He then argued the police could not have a reason to believe he did not possess a valid license to carry. Therefore, the police could not believe he was dangerous if he was possessing a firearm in a legal manner.

This is the crux of the argument that has such a broad impact on any person carrying a firearm, whether legally or illegally. Because of this decision, it is imperative for law enforcement officers and civilians to understand the Court’s ruling and thought-process to make its determination. The interaction of lawfully armed citizens and police can be a positive interaction if both sides understand what the law and the Constitution say about it.

U.S. 4th Circuit Ruling

In examining the case, the 4th Circuit immediately started off with an acknowledgment that car stops are “inherently dangerous” for police officers. The Federal Courts have routinely recognized the dangers that officers face when confronting strangers during enforcement or investigative actions. This is very good for officers, though some civilians may disagree.

The U.S. 4th Circuit turned to the U.S. Supreme Courts rulings to explain, “the risk of a violent encounter in a traffic-stop setting stems not from the ordinary reaction of a motorist stopped for a speeding violation, but from the fact that evidence of a more serious crime might be uncovered during the stop.” (This was from the Supreme Court’s rulings in Maryland v. Wilson and Pennsylvania v. Mimms). In fact, the Supreme Court has acknowledged traffic stops are, “especially fraught with danger to police officers,” going further to add when multiple passengers are involved the threat is increased and the threat is just as great from passengers as it is from the driver themselves.

Despite this ruling, the 4th Circuit recognized that “inherent danger” does not automatically justify a frisk of all occupants without more reasonable suspicion (Terry v. Ohio). In its ruling, the 4th Circuit recognized that the Terry ruling established criteria for evaluating police conduct in stopping and frisking civilians.

Pivotal Legal Precedence on Frisks

However, the 4th Circuit acknowledged the Supreme Court’s ruling in Terry v. Ohio that an officer with reasonable suspicion that criminal activity was afoot was allowed under the 4th Amendment to make an investigatory stop (seizure). In addition, the Supreme Court recognized the “immediate interest of the police officer in taking steps to assure himself that the person with whom he is dealing is not armed with a weapon that could unexpectedly and fatally be used against him (Terry v. Ohio).“

*** This is the pivotal point and legal precedent in U.S. v. Robinson (2017). The 4th Circuit Court evaluates the danger inherent in a “forced” police encounter, just like the Supreme Court evaluated the Terry v. Ohio encounter. In so doing, the 4th Circuit adopted the “now well-known standard that an officer can frisk a validly stopped person if the officer reasonably believes that the person is ‘armed and dangerous’ (Terry v. Ohio).”

Due to the U.S. Supreme Court ruling in the Terry case, the U.S. 4th Circuit Court of Appeals ruled, “when the officer reasonably suspects that the person he has stopped is armed, the officer ‘is warranted in the belief that his safety … [is] in danger, thus justifying a Terry frisk.” The Court, in effect, combined the “armed and dangerous” requirement of Terry from the simple perspective that if a person has a firearm (weapon) on their person they can be dangerous.

In essence, the U.S. 4th Circuit is allowing officers to frisk persons they have a reasonable belief are armed, despite the fact the citizen may be abiding by their State law for concealed or open carry of firearms. This has the potential of creating a confrontation between a police officer performing their duties, and a lawful citizen legally carrying a firearm. As such, an understanding of the 4th Circuit’s reasoning, and how it applies to both police and citizen actions during a contact, is imperative.

Officers should remember concealed carry permit holders are extremely law-abiding, and their oath of office requires them to protect the individual rights of citizens. Citizens must recognize the inherent dangers officers face with enforcement contacts, and understand the courts provide fairly wide latitude for officers to protect themselves. The biggest take from all of this is communication is key.

The citizen should refrain from sudden or furtive movements, and keep their hands clearly visible to the officer. If the officer asks about weapons, the citizen should be honest and indicate where the weapon is located. Citizens should be prepared and willing to obey lawful directions from the officer regardless of whether they have a weapon or not.

Officers need to be cognizant of their local laws on citizens carrying firearms. If the person is abiding by the law, the officer should be hesitant to require invasive actions on the citizen’s part, simply in the over-used “officer safety” guise. There are several safe methods to interact with lawfully armed citizens that will provide the utmost officer safety, and at the same time provide the citizen with the highest level of respect and individual rights protection.

For more information see our upcoming article, Concealed Carry and Police Encounters.

Supportive Consideration by the 4th Circuit

In making their ruling in U.S. v. Robinson, the U.S. 4th Circuit looked to Pennsylvania v. Mimms. The Mimms case was decided by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1977 and is one of the pivotal legal precedents in the direction to police officers when conducting vehicle stops.

In the Mimms incident, an officer stopped Mimms and noticed a large bulge in his jacket. The officer then conducted a frisk of Mimms (based upon Terry v. Ohio) and located a concealed firearm. The U.S. Supreme Court ruled the frisk was clearly justified, further explaining, “the bulge in the jacket permitted the officer to conclude that Mimms was armed and thus posed a serious and present danger to the officer.”

During the Mimms stop, the only indication that Mimms was armed was the bulge in his jacket. There had been no dialogue or other indicators to support the frisk. However, the Supreme Court upheld the frisk as lawful, even going so far as to state, “in these circumstances, any man of ‘reasonable caution’ would likely have conducted the ‘pat down.'”

Since the Supreme Court was acknowledging that Mimms’ status of potentially being armed (the large bulge) was the only factor necessary under Terry v. Ohio to permit a frisk, then Robinson’s failure to answer the question on his being armed, in concert with his “oh crap” look, was sufficient for the officer to consider him armed and dangerous and perform the frisk.

In fact, the U.S. 4th Circuit had ruled on a case similar to the Mimms case (U.S. v. Baker, 1996), and laid a foundation for the ruling in Robinson. In the Baker case, the 4th Circuit cited the Mimms decision recognizes the danger to officers during forced police encounters. The 4th Circuit quoted the Mimms Court, “based on the inordinate risk of danger to law enforcement officers during traffic stops, observing a bulge that could be made by a weapon in a suspect’s clothing reasonably warrants a belief that the suspect is potentially dangerous, even if the suspect was stopped only for a minor violation” (emphasis added).

U.S. Supreme Court Rules for Frisking

Therefore the 4th Circuit ruled the frisk of Robinson was legally permitted because the officers had conducted a lawful stop and presented reasonable evidence of their belief Robinson was armed and thus dangerous. The 4th Circuit then highlighted the U.S. Supreme Court’s rules for conducting a Terry frisk:

- The officers have conducted a lawful stop, which includes both a traditional Terry (reasonable suspicion stop) as well as a traffic stop (observed violation).

- During the valid but forced encounter (stop), the officer reasonably suspects the person is armed and therefore dangerous.

The 4th Circuit then ruled Robinson’s frisk met both legal standards and was therefore lawful.

Legality of Frisks Despite Concealed Carry Laws

In addition to Robinson’s argument on the justification of the frisk itself, the Court ruled on Robinson’s appeal concerning West Virginia’s law allowing for the carrying of concealed firearms.

In his argument, Robinson claimed that since West Virginia law allowed citizens to lawfully carry concealed firearms with a permit, there was no way for the officer to know Robinson did not possess a concealed firearm permit. Since it was possible Robinson was lawfully carrying a firearm under a West Virginia concealed carry permit, then the officer could not have reasonably viewed him as “dangerous” considering he may have been acting lawfully.

In short, the 4th Circuit (quoting Supreme Court rulings) ruled Robinson’s argument fails to overcome the Supreme Court’s express recognition that the legality of the frisk does not depend on the illegality of the firearm’s possession. The key legal principle the 4th Circuit used in making this decision is the two previous Supreme Court rulings expressly allowing the frisk, because “the purpose of this limited search (frisk) is not to discover evidence of crime, but to allow the officer to pursue his investigation without fear of violence.”

The 4th Circuit continued in its reasoning stating, “thus the frisk for weapons might be equally necessary and reasonable, whether or not carrying a concealed weapon violated any applicable state law.” In fact, the U.S. 4th Circuit had previously ruled, “we have expressly rejected the view that the validity of a Terry search (frisk) depends on whether the weapon is possessed in accordance with state law.”

Therefore, the legal precedent in the U.S. 4th Circuit is a legally possessed firearm that poses just as much potential for violence to an officer as an illegally possessed firearm. The Court does not distinguish the potential harm of the firearm, but instead simply acknowledges that firearms can be dangerous. The purpose of the frisk (meeting the two U.S. Supreme Court guidelines) is to allow an officer to complete their investigation without fear of violence.

Robinson’s appeal failed in its entirety. Therefore the officers’ actions to stop the vehicle Robinson was traveling in, and to frisk him based on their reasonable suspicions he was armed (and dangerous), did not violate Robinson’s 4th Amendment rights to be free from unreasonable search and seizures. Therefore, Robinson’s conviction of being a felon in possession of a firearm was upheld, and he was properly sentenced to Federal prison.

Final Thoughts

The laws concerning concealed carry of a firearm have been greatly expanding throughout the United States over the last 25 years. Every State now has a concealed carry permit law, though several (California, Illinois, Hawaii) are still extremely restrictive about who and how a citizen can obtain one.

Understanding the legal landscape is an absolute must for anyone carrying a concealed firearm. This is particularly true for the law enforcement officers charged with upholding those laws. Knowing how to navigate State laws within Constitutional protections can sometimes be a fine line. Anyone carrying a firearm should be a constant student of the practice.

Though U.S. v. Robinson provides allowances for officers to frisk persons lawfully stopped and reasonably believed to be armed, the practice of frisking an otherwise lawful citizen should be reserved for the most extreme and compelling cases. For more information on our guidelines and recommendations, see our article Concealed Carry and Police Encounters.