Information presented in this article is for discussion purposes only. It is not legal advice. You should consult with your department’s legal counsel before doing anything.

The United States Supreme Court has ruled on another use of K-9 units at traffic stops that will have significant impact on the way law enforcement can use this vital tool in the detection and apprehension of illegal drugs. Though the use of police canines has been legally acceptable for nearly 100 years, and has been recognized by the High Court in the use of drug detection for decades, the High Court has made a clear guideline for when their use is lawful and when it is not.

In the April Supreme Court ruling of Rodriguez v. United States, the Court decided the use of a K-9 at a traffic stop can violate the 4th Amendment protections against unreasonable searches and seizures. The decision is not a landmark case, like Arizona v. Gant (where search of vehicles incident to arrest was reversed after 100 years), but the decision solidifies a previously determined concept that traffic stops cannot be extended without additional lawful reasons.

Historical Supreme Court Rulings on K-9 Sniffs

As recent as the Supreme Court case of Illinois v. Caballes, 543 U.S. 405 (2005), the Supreme Court ruled that using a K-9 to conduct a sniff of a lawfully stopped vehicle, did not violate the 4th Amendment’s protection from unreasonable searches, so long as the use of the K-9 does not unreasonably prolong the length of the stop. In this particular case, an Illinois State Trooper stopped Caballes for speeding. Another State K-9 Trooper heard the stop and immediately responded.

While the initial Trooper had Caballes in his patrol car to complete a warning citation, the K-9 Trooper arrived and conducted a sniff of Caballes’ vehicle. The K-9 alerted on Caballes’ vehicle establishing probable cause to search. Inside the trunk, the Troopers located a large amount of illegal drugs. The arrival and sniff of Caballes’ vehicle occurred within 10 minutes of the original stop. Both the Trial and Appellate Courts agreed that the K-9 sniff had not prolonged the stop, and affirmed Caballes’ conviction on drug trafficking charges. However, the Illinois Supreme Court ruled that the K-9 sniff, without articulable reasonable suspicion, enlarged the scope of the stop and therefore was an “unreasonable search” (completely sidestepping the time element for the K-9 search).

The U.S. Supreme Court took the case to determine if a K-9 sniff under such circumstances violated the 4th Amendment. The Court decided that the K-9 arriving and searching within 10 minutes of the stop did not prolong the stop. As far as the expansion of the investigation into a drug investigation without reasonable suspicion, the Court reasoned that in order for the K-9 search to be unlawful during the time of a lawful stop, the search would have to violate a reasonable expectation of privacy. Since the K-9 was searching for the odors of illegal drugs, a person cannot have a legitimate expectation of privacy since it is illegal to possess contraband. Since the Official conduct didn’t invade a reasonable expectation of privacy, the K-9 sniff is not a “search” under the Fourth Amendment parameters. As such, Caballes’ conviction was upheld.

The Application of Reasonableness and Time in Rodriguez v. United States

The Rodriguez case started just after midnight on March 27, 2012, when Officer Struble observed a Mercury Mountaineer veer slowly onto the shoulder of Nebraska Highway 275 for one or two seconds before jerking back onto the roadway. This action was a violation of Nebraska law prohibiting driving on highway shoulders, and led Officer Struble to initiate a stop of at 0006 hours Officer Struble was a K-9 officer for the Valley, Nebraska Police Department, and his K-9 Floyd was with him. Inside the Mountaineer were driver, Dennys Rodriguez, and front-seat passenger, Scott Pollman.

Officer Struble conducted a passenger side approach, and asked Rodriguez why he had driven onto the shoulder. Rodriguez stated he had swerved onto the shoulder to avoid a pothole. After obtaining Rodriguez’s license, registration, and proof of insurance, he asked Rodriguez to accompany him to the patrol car. Rodriguez asked if he was required to, and when Officer Struble advised he was not, Rodriguez chose to wait in his own vehicle.

A records check on Rodriguez did not reveal any violations, so Officer Struble returned to the Mountaineer. Officer Struble asked passenger Pollman for identification, and asked him about where the two were coming from and where they were going. Up to this point, Officer Struble was following standard drug interdiction techniques.

Passenger Pollman said they had gone to Omaha to look at a Ford Mustang that was for sale and they were returning to Norfolk, Nebraska. Officer Struble went back to his patrol car, to complete a records check on Pollman, and call for a backing officer. Officer Struble completed a warning ticket for Rodriguez, and then returned to Rodriguez’s vehicle a third time to issue the written warning. By 0027 or 0028 hours, Officer Struble had finished explaining the warning to Rodriguez, and returned the identification and documents to the occupants.

As Officer Struble later testified, at that point, Rodriguez and Pollman “had all their documents back and a copy of the written warning. I got all the reasons for the stop out of the way…took care of all the business.” Nevertheless, Officer Struble did not consider Rodriguez “free to leave.”

EDITOR’S NOTE: This is the pivotal point of the investigation that weighed into the Supreme Court’s ruling that the continued detention for the K-9 sniff, and subsequent illegal drug discovery, were unlawful under the 4th Amendment. This is in line with the Caballas decision, and several other Supreme Court decisions on prolonging stops.

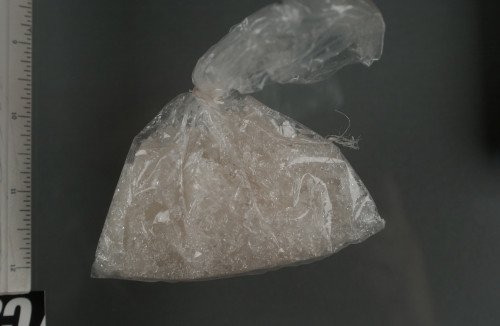

Although justification for the traffic stop was “out-of-the-way,” Officer Struble requested consent to walk his K-9 around Rodriguez’s vehicle, which Rodriguez refused. Despite this, Officer Struble instructed Rodriguez to turn off the ignition, exit the vehicle, and stand in front of the patrol car to wait for the second officer. At 0033 hours, a deputy sheriff arrived to assist. Officer Struble retrieved his K-9 and led him around the Mountaineer twice, when the K-9 alerted to the presence of drugs halfway through Struble’s second pass. Around seven to eight minutes had elapsed from the time Struble issued the written warning until his K-9 indicated the presence of drugs. A search of the vehicle revealed a large bag of methamphetamine.

Drug Interdiction Training Downfall

Unfortunately, Officer Struble was conducting a textbook drug interdiction investigation. These types of techniques have been taught all over the country by a wide variety of drug interdiction officers, and it is very likely that Officer Struble had attended one of those courses. In 1998 I attended one of the DEA Operation Pipeline drug interdiction courses. It was a 3-day training session sponsored by the DEA, and included instruction from Assistant U.S. Attorneys.

During the training course, around six drug interdiction officers (mostly State Troopers) came in and explained their methods for finding “big dope”. These officers were pulling in hundreds of pounds of marijuana, cocaine, methamphetamine and heroin, and their seizures also included millions of dollars. Some of their cases had reached the Federal Appellate Courts and been successful.

The thought was that if an officer gave everything back to the driver, and “ended” the stop, then asking them for consent to search would catch them in an unguarded position that would likely result in a “yes”. In addition, the argument was that this conversation was a “voluntary contact” and therefore eliminated any 4th Amendment concerns. These are the same techniques that Officer Struble conducted during the Rodriguez stop, and the very techniques the U.S. Supreme Court has adamantly rejected as being lawful.

The U.S. Supreme Court Draws the Line

“In Illinois v. Caballes, 543 U. S. 405 (2005), this Court held that a dog sniff conducted during a lawful traffic stop does not violate the Fourth Amendment’s proscription of unreasonable seizures. This case presents the question whether the Fourth Amendment tolerates a dog sniff conducted after completion of a traffic stop. We hold that a police stop exceeding the time needed to handle the matter for which the stop was made violates the Constitution’s shield against unreasonable seizures.”

In its reasoning the Court noted that traffic stops and Terry-stops are relatively brief encounters that have a particular law enforcement mission. The Court stated the tolerable duration of these type of stops is determined by the particular mission. In this case, the Court determined the mission was to address the traffic violation that justified the stop to begin with.

The Court wrote: “Authority for the seizure thus ends when tasks tied to the traffic infraction are, or reasonably should have been, completed.”

Lawfully Permitted Investigations and K-9 Use at Stops

The U.S. Supreme Court affirmed that certain unrelated investigations, such as speaking with a passenger or having a K-9 walked around the vehicle, during the time while an officer is writing the ticket are Constitutionally permissible.

“The seizure remains lawful only so long as [unrelated] inquiries do not measurably extend the duration of the stop.”

The High Court noted, and the government conceded, that a K-9 sniff is not an “ordinary incident of a traffic stop.” The majority made a point of noting that the question for 4th Amendment purposes is not whether the dog sniff occurs before or after the completion of a routine traffic stop, instead the question is whether the dog sniff added time to the length of the otherwise lawful stop.

Final Considerations on Lawful K-9 Uses

- Any action, which measurably prolongs a stop beyond the law enforcement mission that justified the stop to begin with will invalidate the additional enforcement action – period.

- Prolonging a stop beyond the initial law enforcement mission requires reasonable suspicion or probable cause developed beyond the reason for the initial stop to support the continuation of the stop.