The United States Supreme Court (USSC) has just issued a ruling in consideration of the application of Implied Consent laws when collecting a blood sample to determine a suspect’s blood alcohol concentration (BAC). In a decision that will have a significant impact on every law enforcement agency in America, the Supreme Court has ruled warrantless blood draws violated the 4th Amendment when taken under Implied Consent laws that enforce criminal penalties for refusal.

Not all States criminalize the refusal to submit to a chemical test, but there are several that do. The Supreme Court has held that a blood test is more intrusive than a breath test and therefore a warrantless blood test is impermissible under Implied Consent when refusal to submit is criminalized.

Blood Draws and Implied Consent

Though the number of DUI fatalities has decreased over 50% during the last 30 years, the problem of impaired driving continues to be a top traffic safety priority in many jurisdictions. As States have created stricter penalties for subsequent DUI charges, many suspects are refusing chemical testing. In response to rising refusals, many States have imposed a criminal penalty for refusing a chemical test.

The Supreme Court accepted certiorari of (3) State Supreme Court cases to determine the legality of obtaining blood samples under criminal penalty of refusal. In three separate cases, one from Minnesota and two from North Dakota, the U.S. Supreme Court held that a blood test is more intrusive than a breath test. Therefore, Implied Consent laws compelling a driver to provide a blood sample under criminal penalty of refusal would violate the 4th Amendment.

During its deliberations the U.S. Supreme Court recognized the problem of impaired driving in America. The Court acknowledged many states and the U.S. Government had increased penalties for DUI to combat impaired driving. In addition, several States had criminalized refusing to be tested following an arrest. The Court noted there had been an increase in refusals over the last few years due to the severity of penalties for actual DUI charges. One study reported over 20% of arrested drivers in 2011 refused to submit to testing. Minnesota and North Dakota were two of the States that criminalized the refusal to submit to chemical testing under Implied Consent.

The Three Cases Considered

Birchfield v. North Dakota

On October 10, 2013 Birchfield drove his car off a North Dakota highway. A smelled a strong odor of an intoxicating beverage, and noted Birchfield’s eyes were bloodshot and watery. When Birchfield spoke his speech was slurred, and he had difficulty maintaining his balance standing up. The Trooper administered sobriety tests and Birchfield showed impairment on each test.

The Trooper believed Birchfield was intoxicated and informed him of his obligation to submit to a chemical test under State law. Birchfield consented to a roadside breath test which indicated impairment, but could not be used as an evidentiary finding by State law. Instead, the Portable Breath Test (PBT) was only allowed to determine if further testing was warranted. Birchfield’s PBT test estimated his BAC at 0.254%.

Birchfield was arrested for driving while impaired, provided Miranda warnings, and again advised of his obligation under North Dakota law to undergo BAC testing. Birchfield was also informed refusing to take the test would expose him to criminal penalties. Penalties increased for repeat offenders, and the penalty for refusing a chemical test applied to blood, breath, urine, and saliva testing.

Birchfield refused the blood test despite the penalty to do so. Three months prior to this case Birchield had been arrested for DUI and had already pled guilty. Birchfield pled guilty to the misdemeanor violation of the refusal statute, but was conditional on the argument the 4th Amendment prohibited criminalizing his refusal to submit to the test. The State District Court rejected this argument and imposed a 30 day in jail sentence (20 days suspended) and $1750 in fines, due to his previous DUI conviction.

Bernard v. Minnesota

On August 5, 2012, St. Paul, Minnesota Police responded to a disturbance at a boat launch. Three intoxicated men got their truck stuck in the river while attempting to pull their boat out of the water. Witnesses identified the driver as Bernard. Bernard admitted that he had been drinking but denied driving the truck (though he was holding its keys), and refused to perform any field sobriety tests. Officers smelled alcoholic beverages on Bernard’s breath, and observed his eyes were bloodshot and watery. Bernard was arrested for driving while impaired.

At the police station officers read Bernard Minnesota’s implied consent, informing him it is a crime under State law to refuse to submit to a legally required BAC test. In addition to non-criminal penalties like license revocation, test refusal in Minnesota can result in criminal penalties ranging from imprisonment to fines. Bernard refused to take the test, and prosecutors charged him with test refusal in the first degree because he had (4) prior DUI convictions. First-degree refusal carries the highest maximum penalties and a mandatory minimum 3-year prison sentence.

The Minnesota District Court dismissed the refusal charges, ruling the warrantless breath test demanded of Bernard was not permitted under the 4th Amendment. The Minnesota Court of Appeals reversed that decision, and the State Supreme Court affirmed the Appeals Court. Based on the longstanding doctrine that authorizes warrantless searches incident to a lawful arrest, the Minnesota high court concluded police did not need a warrant to insist on a test of Bernard’s breath.

Beylund v. North Dakota

A Bowman, North Dakota Police officer spotted Beylund unsuccessfully attempt to turn into a driveway on August 10, 2013. In the failed turn, Beylund’s car nearly hit a stop sign before stopping partly on the public road. The officer contacted Beylund and observed an empty wine glass in the center console next to him. Beylund smelled of an alcoholic beverage so the officer asked him to step out of the car. Beylund struggled to keep his balance while exiting his vehicle.

The officer placed Beylund under arrest for DUI and took him to a nearby hospital. At the hospital the officer read Beylund North Dakota’s Implied Consent warning, informing him a refusal to take the test was a crime. Unlike the other two other petitioners, Beylund agreed to have his blood drawn and analyzed. A nurse took a blood sample, which revealed a BAC of 0.250%, more than three times the legal limit.

The test results resulted in Beylund’s driver’s license being suspended for two years after an administrative hearing. Beylund appealed the hearing officer’s decision to a North Dakota District Court, arguing his consent to the blood test was coerced by the officer’s warning that refusing would itself be a crime. The North Dakota District Court rejected this argument, so Beylund again appealed.

The North Dakota Supreme Court affirmed the District Court’s ruling. In response to Beylund’s argument that his consent was insufficiently voluntary, the North Dakota Supreme Court referred to the then-recent Birchfield decision, and another previous decision, upholding the Constitutionality of those penalties.

U.S. Supreme Court Certiorari

The three cases mentioned above were consolidated to decide whether motorists lawfully arrested for DUI may be convicted of a crime or otherwise penalized for refusing to take a warrantless test measuring the alcohol in their bloodstream. What would no doubt become a pivotal part of this review was the U.S. Supreme Court decision in Missouri v. McNeely (2013). In that case the Court held “the natural dissipation of alcohol in the bloodstream does not constitute an exigency in every case sufficient to justify conducting a blood test without a warrant.” A Missouri State Trooper had arrested a driver for DUI, and compelled a blood draw based upon a believed “exigent circumstances” (BAC dissipating) exception to the 4th Amendment.

The three cases differ in some respects. Petitioners Birchfield and Beylund were told they were obligated to submit to a blood test, whereas petitioner Barnard was informed that a breath test was required. Birchfield and Barnard refused the test and were convicted of the crime for refusal. Beylund complied with the demand for a blood sample, and his license was then suspended in an administrative proceeding based on test results that revealed a very high BAC.

Despite some differences, all three cases challenge the legality of State law compelling a motorist to submit to a blood or breath sample without a search warrant authorizing such testing is issued by a judge. In its review, the U.S. Supreme Court determined the test was a search, so a determination had to be made as to whether the testing process met one of the exceptions to the warrant requirement. The Court focused its analysis on the Search Incident to Arrest exception, and examined the privacy interests at stake in breath tests and blood tests as two distinct tests.

Breath Tests Do Not Require a Warrant

In examining the privacy concerns of breath tests, the Supreme Court held breath tests do not achieve a strong privacy interest that would overcome legitimate government interests. The Court stated the “physical intrusion is almost negligible,” and “breath tests do not require piercing the skin and entail a minimum of inconvenience.” In particular the Supreme Court noted breath tests gather only a single bit of information, the BAC, rather than the wide variety of personal medical information that can be obtained from a blood sample.

The Court concluded breath tests meet the Search Incident to Arrest exception to the 4th Amendment, and the criminalization of refusal to take a breath test would not violate the 4th Amendment’s warrant requirement.

- Breath tests are less intrusive than blood tests

- Government interest for breath tests outweigh privacy concerns

- Breath tests only provide BAC, specific information to the charge

- Breath tests are supported by the Search Incident to Arrest exemption

- The 4th Amendment allows criminal and civil penalties for breath refusals.

Blood Tests Require a Search Warrant

On the other hand, the Supreme Court ruled a blood test did implicate a significant privacy interest, and concluded that Search Incident to Arrest would not justify a forced blood test. That “force” could be implied by the coercion of criminal penalties simply for refusing the more intrusive blood test.

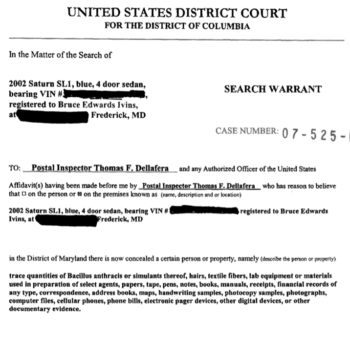

Therefore, for officers to obtain a blood sample from a suspect they must either gain consent (absent of a criminal penalty for refusing), or secure a search warrant for the blood based upon probable cause and signed by a judge.

In my State we have increasing penalties for subsequent DWI convictions. The first two DUI convictions are misdemeanors, but a third offense becomes a lower felony. However, a 4th, 5th, and additional convictions can result in a mid to high level felony penalties with sentences up to 15 years in prison. This is separate from penalties involving injuring or killing someone while operating a motor vehicle in an impaired condition.

Refusals for breath and blood have gone dramatically up. So far our State Prosecutor will go forward with DUI prosecution on misdemeanor arrests with a refusal. However, once the charge becomes a felony, a refusal will generate a search warrant. Blood is then drawn three (3) times in an hour, at half hour intervals to document BAC rise or fall.

- Blood tests are more intrusive than breath tests

- Blood tests require piercing the suspect’s skin

- Personal medical information outside of BAC can be obtained from blood

- Privacy concerns outweigh government interest, without a warrant

- The 4th Amendment does not support criminal penalties for refusing a blood test

- Consent for blood can only be valid if no criminal penalty for refusal is present

- Obtaining a blood sample requires a search warrant without proper consent.

Implied Consent Considerations

The Supreme Court then turned to the concept of Implied Consent and whether forced blood testing was justified based on a driver’s implied consent under driver’s licensing statutes. The Supreme Court made particular note that the decision in this case had nothing to do with refusals under State law using implied consent where the penalty is civil in nature only.

In States where the penalty for refusing a chemical test is a civil action against the driver’s operator license, the Supreme Court very clearly ruled this was lawfully permissible under the 4th Amendment. In addition, in those States where the refusal is a civil action, there is no 4th Amendment prohibition that officers obtain a search warrant for blood after the refusal, and then proceed with a criminal proceeding for DUI and license revocation.

In those cases the Supreme Court makes a distinct separation of the criminal proceeding for DUI, and the administrative civil action against a person’s driver’s license for refusing the chemical test under Implied Consent laws.

However, the Supreme Court said, “it is another matter, however, for a State not only to insist upon an intrusive blood test, but also to impose criminal penalties on the refusal to submit to such a test. There must be a limit to the consequences to which motorists may be deemed to have consented by virtue of a decision to drive on public roads.”

The Court concluded that Implied Consent laws “cannot be deemed to have consented to submit to a blood test” where the penalties are criminal in nature. This decision was based on the Supreme Court’s separation of the intrusiveness of breath versus blood tests. Since blood test require piercing the suspect’s skin, and collecting blood that can contain a far greater amount of personal medical information than breath, the Court determined only a search warrant would satisfy the 4th Amendment in those circumstances.

The Court held that Birchfield was arrested and charged for refusing a blood test. Thus in his case the case was contrary to the 4th Amendment since neither Implied Consent nor Search Incident to Arrest would justify the search.

Bernard was charged for refusing to take a breath test. The Court concluded that such a test is justified under the Search Incident to Arrest exception of the 4th Amendment, and so his arrest, charging and conviction was upheld.

The Court also threw out Beyland’s prosecution, because he was told that he was required by law to submit to the blood test. Therefore his participation in the blood test was not consensual as it was in the Birchfield case, the test was not justified by Implied Consent and did not meet the Search Incident to Arrest exception.

Supreme Court Ruling Matrix

- Blood Tests with criminalized Implied Consent refusals violate the 4th Amendment

- Breath Tests with criminalized Implied Consent refusals are allowed

- This Case has NO IMPACT in States where refusal only results in civil action.

Final Thoughts

The U.S. Supreme Court has definitively separated the breath test and the blood test in DUI investigations. The administration of a breath test remains intact, and the Court has ruled the both civil and criminal penalties are justified under the 4th Amendment for a refusal to submit to a breath test.

However, a blood test is far more intrusive than a breath test. In order to obtain a lawful blood sample, officers must obtain valid consent or a search warrant signed by a judge. Suspect’s cannot give valid consent, if the State makes their refusal to submit to a blood test criminal. However, if refusing a blood test results in merely civil action against the driver’s license, the Supreme Court has ruled the action is supported by the 4th Amendment.

The Supreme Court was very careful to lay out the differences required in imposing criminal penalties for refusing a breath or blood test. In addition, with the ruling in Missouri v. McNeely (2013), officers are on notice they may not force a blood test on a suspect without a search warrant.

In short, if there is any doubt when seeking a blood sample – GET A SEARCH WARRANT!