The information presented in this article is for discussion purposes only. It is not legal advice. You should contact your department’s legal counsel for guidance on the topics presented by the author.

On November 14, 2014 the U.S. 1st Circuit Court of Appeals decided an appeal to a case involving the reasonable suspicion investigation of officers assigned to a High Intensity Drug Trafficking Area (HIDTA) Task Force in Rhode Island. The case involves the outstanding documentation of the officers observations of suspicious behavior up to and including the first contact with the defendant.

These observations laid a strong foundation of reasonable suspicion, leading up to the officers stopping and detaining the defendant Fermin. As a result of the investigation Fermin was charged with Federal drug trafficking and weapons charges. The U.S. 1st Circuit Court of Appeals reasoning of the officers’ actions is a great review of how officers can investigated suspicious behavior that does not rise to the level of probable cause or an observed violation of law.

Facts of the Investigation

This case stemmed from a January, 2012 investigation where officers observed Fermin acting suspiciously around the Providence College campus in Providence, Rhode Island. A specific house near the college campus had been identified with an illegal drug problem, and the officers were conducting surveillance in the area to develop leads.

Fermin was observed walking down a sidewalk wearing a trash bag underneath his sweatshirt. Though the investigation was in January and temperatures were likely very cold, wearing a trash bag underneath clothing is not a common method of fighting the cold and one of the first “suspicious” activities documented by officers.

At some point Fermin abruptly exits the sidewalk and suddenly ducks between two houses. Fermin did not go to the front door of a residence, and instead walked between two houses. This type of behavior can be seen as “suspicious” as it does not appear that Fermin is going somewhere that he is authorized.

A few minutes later Fermin reappeared rolling a suitcase. This was the second piece of “suspicious” behavior observed by the officers, since it is a very uncommon event for someone to walk between houses and suddenly reappear with a suitcase. Most citizens with suitcases originate from a vehicle or actual residence, and not from between two houses, as if the case was pre-positioned there.

Fermin began looking around “as if to check if anyone was walking behind him”. This is “suspicious” act number 3, and one that veteran officers can clearly link to illegal behavior. Suspects worried about being discovered in their criminal actions, often keep looking around for police, witnesses, or rival illegal participants. This type of behavior is often described as “shifty”.

Fermin then walked the suitcase into the far end of a parking lot and placed the suitcase between a vehicle and a dividing wall. He was then observed walking away from the case and talking on a cell phone. Here is another classic “suspicious” behavior by Fermin. Most citizens do not retrieve a suitcase and then very shortly afterwards go into a parking lot and “hide” the suitcase in the deep corner between a Jeep and a dividing wall.

After several separate conversations on his cell phone Fermin moved the suitcase underneath a Jeep, and then later took his sweatshirt off and tied it to the suitcase’s handle. Several minutes later Fermin retrieved the suitcase and exited the parking lot pulling the suitcase behind him. Another “suspicious” action by Fermin, noted by the officers.

Investigative Detention Based Upon Reasonable Suspicion

By this time the officers felt they had enough to stop Fermin and investigate more directly. A review of the facts of the investigation builds a strong foundation to support the officers’ claims, and their documentation of those observations in police reports will be critical to a successful outcome in court.

The reasonable suspicion observations to this point:

- Fermin is observed walking in an area under investigation for illegal drugs

- Fermin was observed wearing a trash bag underneath his sweatshirt

- Fermin abruptly walked between two houses, not to a particular residence

- One of those residences was the specific house under investigation

- Upon returning, Fermin is seen walking with a suitcase in tow

- Like many criminals, Fermin is observed looking all around, like someone is watching him

- Fermin immediately walks into the deep corner of a nearby parking lot

- At that time Fermin is observed hiding the suitcase while talking on his cell phone

- Suddenly Fermin ties his sweatshirt to the suitcase

- Finally, Fermin retrieves the stashed suitcase and begins walking away again.

Arrest Based Upon the Probable Cause Discovery of Marijuana

Upon contact, Fermin immediately dropped the suitcase and stated that it was not his. In fact, he lied and said that he had been running on the Providence College track when someone threw the suitcase over the fence and he took the suitcase.

NOTE: The U.S. Supreme Court and Appellate Courts have consistently ruled that abandoned property does not hold the same levels of 4th Amendment protections as property still claimed by an owner. As such, when a person abandons property (as Fermin did), and especially after they claim no ownership in the item (as Fermin did), than the property can be considered abandoned and searched outside of normal 4th Amendment requirements. See CALIFORNIA v. GREENWOOD, 486 U.S. 35 (1988).

While standing near Fermin and the suitcase one of the officers could smell a “strong odor” of marijuana coming from the suitcase. Based upon probable cause (the smell of marijuana inside the suitcase), the officer opened the suitcase and discovered a large amount of marijuana contained inside. At that time Fermin was placed under arrest and transported to a State Police barracks for interrogation.

During the interrogation Fermin again stated that he has just found the suitcase after someone threw it over the fence at the Providence College track, and a friend encouraged him to take it to see if there was any money inside. However, Fermin refused to identify his “friend”. When confronted with surveillance photographs showing him to be alone when the suitcase was brought out from between the houses, Fermin became “visibly upset”, advising the officers that he did not want to argue.

Evidence Discovered During Investigation

During the investigation Police recovered the following illegal items from the suitcase:

- 33 pounds of marijuana stored in 38 plastic zip-lock bags

- 31 grams of cocaine

- A bottle of powdered caffeine

- 3 digital scales

- A box of plastic bags like the ones filled with marijuana

- A .357 revolver loaded with 6 rounds of ammunition inside a rolled-up pair of sweatpants.

The Conviction and Appeal of Fermin

Fermin was charged with Federal drug and weapon offenses. He filed a motion to suppress arguing that the task force officers did not have reasonable suspicion to justify stopping him. The U.S. District Court denied the motion to suppress, and Fermin was convicted at trial. He then filed a timely appeal to the First Circuit Court of Appeals, and argued, among other things, that the District Court erred in denying his motion to suppress.

The District Court held that the agent’s initial encounter with Fermin was a consensual encounter and the search of the bag was lawful because Fermin disclaimed ownership, and therefore, privacy in the bag. (This is what was noted earlier in the article concerning “abandoned” property).

The U.S. 1st Circuit Court of Appeals had to decide whether the agent’s performed a consensual contact or an investigative detention of Fermin when he denied ownership of the suitcase. A consensual contact is one where a reasonable person in the same situation, must believe that they are free to leave or decline to speak to the police at any time.

The U.S. 1st Circuit stated:

It is not clear that a reasonable person, surrounded by five police officers, would believe that he was free to leave. See California v. Hodari D., 499 U.S. 621, 627-28 (1991). Indeed, Fermin did not leave but rather submitted to police authority by answering questions about the suitcase. See United States v. Holloway, 499 F.3d 114, 117 (1st Cir. 2007) (citizen’s submission to show of police authority is a prerequisite for a finding of seizure).

Interestingly, the 1st Circuit stated they did not need to decide whether this was a consensual encounter or an investigative detention because sufficient reasonable suspicion existed to support a lawful investigative detention of Fermin. The court stated reasonable suspicion exists when:

Police had “a particularized and objective basis for suspecting [Fermin] of criminal activity.” Ornelas v. United States, 517 U.S. 690, 696 (1996).

The court then listed several relevant facts that they found established reasonable suspicion that Fermin was involved in criminal activity (compare to the list the author provided above):

- Prior to observing Fermin, the police received a tip from a confidential informant that the house located at 40 Liege Street was a stash house for a large amount of marijuana.

- Police then conducted surveillance of the location and observed numerous people coming and going in a manner consistent with drug activity.

- Fermin’s deliberate path toward 40 Liege Street and his disappearance and quick reappearance in that area with the bag in tow was significant.

- Fermin towed the bag to a parking lot and attempted to hide it under a Jeep before picking it back up and continuing on foot with the bag in tow.

The court held that these, facts taken together, amounted to sufficient reasonable suspicion to believe that Fermin may be involved in criminal activity.

Therefore the 1st Circuit held the stop of Fermin was lawful under the 4th Amendment. The court also held the search was lawful because Fermin denied ownership of the suitcase, stating that he had found it, but the suitcase was not his. The court held that he relinquished his privacy interest in the suitcase and the search was lawful.

Accordingly, the 1st Circuit affirmed the denial of the motion to suppress, and Fermin’s convictions for Federal drug and weapons violations were upheld.

The Standard of Police Encounters with Citizens

The standard of police interactions with citizens has been outlined in the 4th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution for 224 years. One of 10 amendments that were critical to the ratification of the U.S. Constitution, the 4th Amendment clearly identifies the Founding Fathers desire to protect the people from over-zealous government intrusion.

Amendment IV, U.S. Constitution:

“The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized.”

The 4th Amendment established clear requirements for government officials (police officers) to seize and search American citizens. Searches could not be random, but were required to be particularly described in place and persons to be searched and seized.

Reasonable Suspicion – Terry v. Ohio

However, it was not until 1968 that the U.S. Supreme Court took on the much more difficult question of when police officers could confront someone who was believed to be involved in criminal activity, but their actions did not rise to the level of probable cause that would warrant their physical arrest.

In the landmark case of Terry v. Ohio (1968), a fairly liberal U.S. Supreme Court confirmed that the officer who detained Terry, and ultimately arrested him on possessing a concealed firearm, had met the “reasonableness standard” as required by the 4th Amendment. This was despite the fact, that the observations of the officer did not meet probable cause to arrest.

In the famous case, the officer observed Terry and others casing a store at night. The officers detailed descriptions of his observations of “suspicious” behavior, including his level of experience, expertise, and knowledge of the neighborhood, all combined to established what the Supreme Court called “reasonable suspicion” that a crime was about to be, was, or had been committed.

Thus the standard of Reasonable Suspicion to justify temporary detentions of citizens, and satisfy the 4th Amendments restrictions on police, was established. In short police must provide the following to satisfy this requirement, and it must go beyond a simple hunch of the officer:

Specific and articulable observations, when taken together, would lead a reasonable officer in similar circumstances to believe that the particular person(s) being detained by police has been, is, or is about to be involved in criminal activity.

This level requires a combination of circumstances, and specifically prohibits taking detention actions based solely on a “hunch”. The courts will review the officers’ actions based on the Reasonableness Standard, requiring the officers to articulate their suspicions, and weighing those observations with what a “reasonable officer” would do in similar circumstances.

In essence, if it looks like a duck, it walks like a duck, and it talks like a duck … there’s a good chance it’s a duck! The same common sense principle was codified by the U.S. Supreme Court over 45 years ago.

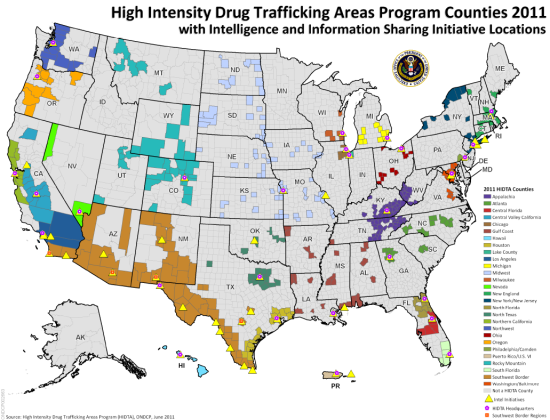

High Intensity Drug Trafficking Areas (HIDTA)

Over 25 years ago the U.S. Congress passed the Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1988, providing assistance to Federal, state, local, and tribal law enforcement agencies operating in areas determined to be critical drug-trafficking regions of the United States.

The purpose of the program is to reduce drug trafficking and production in the United States by:

- Facilitating cooperation among Federal, state, local, and tribal law enforcement agencies to share information and implement coordinated enforcement activities;

- Enhancing law enforcement intelligence sharing among Federal, state, local, and tribal law enforcement agencies;

- Providing reliable law enforcement intelligence to law enforcement agencies needed to design effective enforcement strategies and operations;

- Supporting coordinated law enforcement strategies which maximize use of available resources to reduce the supply of illegal drugs in designated areas and in the United States as a whole.

Having worked for the Midwest HIDTA as an undercover investigator for 2 years, I can say that the funding and coordination between multiple agencies at all levels of law enforcement is critical to the identification, investigation, and dismantling of large-scale drug trafficking organizations.

The drug cartels and their associated networks are most definitely organized crime. To battle such intricate underworld organizations requires even more organization and cooperation on the side of law enforcement. HIDTA areas provide that foundation and funding. In the Southeast HIDTA aggressively went after cocaine trafficking, while those on the West coast worked a variety of illegal drugs, particularly heroin trafficking.

Our particular HIDTA task force focused on methamphetamine manufacturing and distribution in the midwest, that was a scourge in the 1990’s and 2000’s. Our task force was very successful in apprehending meth cooks, pushing most of the remaining cooks to the most rural areas – making distribution much more difficult.

However, the void in “local” cooks created a vacuum that paved the way for “Mexican Meth” to arrive, along with the established networks of the drug cartels. Our HIDTA task force transitioned from hunting the cooks and taking down meth labs, to infiltrating large-scale drug trafficking organizations (DTO’s).

The results were cases that spanned the entire United States, not just our defined working area, and often involved Federal and State search and arrest warrants executed on the same day in many locations across the country. These investigations rose to Federal Conspiracy cases involving dozens of indictments that resulted in very lengthy prison terms for the “leaders” of the DTO’s and millions of dollars in seized drugs, money, and property under forfeiture laws.

The map below shows the HIDTA locations around the U.S.