The information in this article is presented for discussion only. It is not legal advice. You should consult with your department’s legal team before taking any actions.

On April 15, 2015, the U.S. 11th Circuit Court of Appeals decided the case of Mobley v. Palm Beach Sheriff Dept. et al. At question was the reasonableness of force used by deputies while apprehending a suspected criminal at the end of a pursuit. The U.S. 11th Circuit covers Florida, Georgia, and Alabama, and this ruling is binding in that Circuit, however, as with any of the U.S. Courts of Appeals, the decision of one Circuit often weighs heavily in the decision-making of the other Circuits.

Mobley v. Palm Beach Sheriff Department et al.

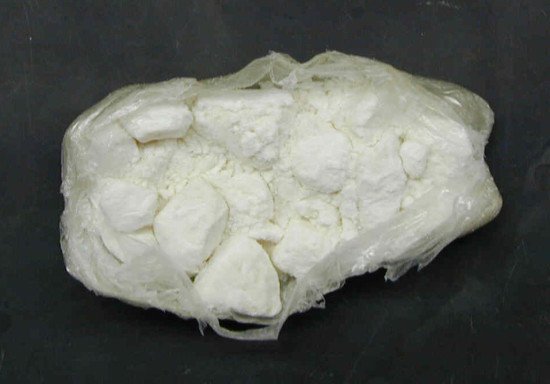

The case started on December 12, 2007. Petitioner Mobley was parked in a West Palm Beach convenience store parking lot, and bent over in the driver’s seat of his truck to smoke crack cocaine. Deputy Bronson of the Palm Beach County Sheriff’s Department was on bicycle patrol with his partner, in response to “complaints of high volumes of drug activity” in the area.

Deputy Bronson was in full uniform when he noticed Mobley’s suspicious behavior. He approached the truck after observing the truck as parked in a handicapped spot and not displaying a handicapped placard. Mobley did not see Bronson approaching his truck, and because he was slouched in the driver’s seat he claimed that he was unable to see anything that identified Bronson as a police officer. Depending on how high the truck was off the ground, that claim may be more reasonable than it sounds at first.

First Contact and Assault

At that time Deputy Bronson asked Mobley, “What are you doing?” Mobley said that he was afraid he was being “robbed again,” and in response he dropped his crack pipe and started his truck. As Mobley was starting his truck, Deputy Bronson reached through the open driver’s side window and grabbed Mobley while attempting to open the driver’s door. Deputy Bronson was still holding onto Mobley, when Mobley was able to place the truck in Reverse, and backed quickly out of the parking space. During the escape, Mobley struck Deputy Bronson with his truck, dragging him approximately 20 feet across the parking lot before Bronson fell clear of the truck.

Mobley fled the parking lot in his truck. While driving away, Mobley admitted that he saw Deputy Bronson standing in the parking lot and pointing a pistol at him. Mobley also admitted that he saw that Deputy Bronson was a uniformed law enforcement officer. As Mobley fled, Deputy Bronson radioed in the assault and Mobley’s fleeing, and provided a description of Mobley and his truck. In the broadcast, Deputy Bronson stated that Mobley had struck him with the truck, tried to run him over, and fled the scene.

The Pursuit, Crash, and Surrender

Mobley only drove a few blocks away and parked his truck, but a Sheriff’s car arrived in the area a short time later and Mobley fled again, with the deputy in pursuit. After driving a few blocks, several additional Sheriff cruisers were engaged in the pursuit. Mobley drove recklessly and at high speeds while trying to evade the pursuing deputies. Mobley was looking back at the police cruisers when his truck ran off the road.

Mobley turned around in time to avoid striking the trunk of a tree. However, the truck struck a tree limb shattering the windshield and collapsing the truck’s roof over the driver’s seat. Despite the serious damage to his truck, Mobley continued driving a short distance further to an open area “out of the traffic” and where there were “lots of light.” Mobley claimed he drove to that area saying he had decided he would surrender there. For reasons that even Mobley could not explain in court, he exited his truck and ran to a small retention pond, wading out to its center.

By the time Mobley had reached the middle of the pond, deputies had surrounded the pond and a Sheriff’s Department helicopter was shining its spotlight on him from overhead. Mobley finally came out of the pond to the waiting deputies on the western bank of the pond. One of the deputies grabbed Mobley’s hair and took him to the ground, ordering him to surrender his hands for cuffing.

While Mobley was on the ground, deputies struck and kicked him, including in his face. Mobley covered his face with his hands. The use of force by the officers broke Mobley’s nose, some teeth, and his plastic dental plate. The officers also used a Taser on Mobley several times while he was on the ground. Mobley eventually gave up, and placed his hands behind his back where he was handcuffed. After being secured in handcuffs, Mobley was given medical attention.

Mobley was transported to St. Mary’s hospital where doctors found he had a broken nose, cuts and bruises along his arms and hands, and broken front teeth. Mobley was later was diagnosed with “Post Traumatic Syndrome” (PTS), and began suffering seizures. In a State criminal trial, Mobley was convicted of assaulting Officer Bronson with a deadly weapon, and fleeing to elude arrest. Mobley was sentenced to 15 years imprisonment.

The Suit Claiming Excessive Force

Mobley contends that eight of the officers were either directly or indirectly involved in his arrest. Deputies Elliott, Johnson, and Yoder physically effected Mobley’s arrest. Lieutenant Burdick was present at the arrest scene, but he was not physically involved in the arrest. Deputies Bronson, Sheehan, and Moore, and Sergeant Clapp were not present at the scene of Mobley’s arrest, but it was Deputy Bronson who had made contact with Mobley to start the events leading to his arrest.

Mobley filed suit against the Sheriff and deputies alleging the deputies used excessive force in effecting his arrest by striking and Tasing him. In response, the deputies filed for summary judgment and qualified immunity. The U.S. District Court held that the force used by the deputies was reasonable, and granted summary judgment for the defendants. Mobley appealed to the 11th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals to determine whether the force used by the officers was reasonable under the 4th Amendment.

Reasoning and Decision of the 11th U.S. Circuit

As is common in legal decisions, especially on the appellate level, the 11th U.S. Circuit noted several legal principles applicable in this case:

- Freedom from unreasonable searches and seizures under the 4th Amendment “encompasses the right to be free from excessive force during the course of a criminal apprehension.” Oliver v. Fiorino, 586 F.3d 898, 905 (11th Cir. 2009).

- The right to make an arrest “necessarily carries with it the right to use some degree of physical coercion or threat thereof to effect it.” Graham v. Connor, 490 U.S. 386, 396, 109 S. Ct. 1865, 1871-72 (1989). EDITOR’S NOTE: This is the pivotal U.S. Supreme Court case in police use of force, and established the concept of “objective reasonableness” as the standard in deciding these cases.

- We judge excessive force claims “under the 4th Amendment’s objective reasonableness standard.” Crenshaw v. Lister, 556 F.3d 1283, 1290 (11th Cir. 2009)

- That standard asks whether the force applied “is objectively reasonable in light of the facts confronting the officer,” a determination we make “from the perspective of a reasonable officer on the scene” and not “with the 20/20 vision of hindsight.”

- We consider factors including “the severity of the crime at issue, whether the suspect poses an immediate threat to the safety of the officers or others, and whether he is actively resisting arrest or attempting to evade arrest by flight.” Graham, 490 U.S. at 396, 109 S. Ct. at 1872.

- We also consider “the need for the application of force, . . . the relationship between the need and amount of force used, and . . . the extent of the injury inflicted.” Lee v. Ferraro, 284 F.3d 1188, 1198 (11th Cir. 2002).

- The U.S. Supreme Court held that the test for excessive force during an arrest is objective reasonableness under the Fourth Amendment. Graham, 490 U.S. at 397, 109 S. Ct. at 1872. “An officer’s evil intentions will not make a 4th Amendment violation out of an objectively reasonable use of force; nor will an officer’s good intentions make an objectively unreasonable use of force constitutional.”

- If an officer reasonably, but mistakenly, believed that a suspect was likely to fight back . . . the officer would be justified in using more force than in fact was needed. Pearson v. Callahan, 555 U.S. 223, 129 S. Ct. 808 (2009); Graham, 490 U.S. at 396-97, 109 S. Ct. at 1872

- “The calculus of reasonableness must embody allowance for the fact that police officers are often forced to make split-second judgments in circumstances that are tense, uncertain, and rapidly evolving about the amount of force that is necessary in a particular situation.”

Mobley attempted to use two cases which he claimed supported his claim of excessive force. However, Slicker v. Jackson, the plaintiff was already arrested and handcuffed when officers beat his head on the ground and kicked him in the ribs. In the second case, Reese v. Herbert the District Court ruled that any force used against a person, when no probable cause existed for arrest, was unreasonable. The 11th U.S. Circuit ruled this case was not applicable to Mobley because there was probable cause to arrest him for very serious offenses.

The Pivotal Point of Reasonable Force

The 11th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals then stated:

Our decisions demonstrate that the point at which a suspect is handcuffed and “pose[s] no risk of danger to the officer” often is the pivotal point for excessive-force claims.

In addition, the Court stated, we have held a number of times that severe force applied after the suspect is safely in custody is excessive. See Galvez v. Bruce, 552 F.3d 1238, 1243 (11th Cir. 2008); Lee, 284 F.3d at 1198; Slicker, 215 F.3d at 1233.

Force applied while the suspect has not given up and stopped resisting and may still pose a danger to the arresting officers, even when that force is severe, is not necessarily excessive. See Crenshaw, 556 F.3d at 1294; cf. Zivojinovich v. Barner, 525 F.3d 1059, 1073 (11th Cir. 2008) (use of taser on a handcuffed suspect was not excessive when officer reasonably believed that suspect “who ha[d] repeatedly ignored police instructions and continue[d] to act belligerently toward police” was spitting blood on him).

Based upon the facts of Mobley’s case and the legal principles laid out by the 11th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, the Court held that the deputies did not violate Mobley’s 4th Amendment rights because the force used was objectively reasonable. Therefore, they affirmed the grant of summary judgment and qualified immunity for the deputies. In essence, the Court found the deputies had done no wrong.

The important concept to take from this very important decision is the pivotal point in the court’s decision-making process of reasonable force – whether the suspect had been handcuffed. However, also of significant importance is the crime the suspect is alleged to have committed, and the level of force or resistance being offered by the suspect – even if they are handcuffed.

The Use of Force can never be an enactment of punishment. That is the Court’s job!

Final Thoughts and a Word of Caution

The comedian Chris Rock famously quipped, “everybody knows, if the police have to come and get you, they’re bringing an ass kickin’ with them”. I admit that I found that act very funny, and the pointers he gave were actually very legitimate advice to avoid trouble with the police. However, there are too many officers that believe Chris Rock’s concept is an absolute rule, or a freebie for force.

As professionals, officers are expected to overcome resistance using legitimate force, but also recognize when the suspect has ceased resistance and can be secured in handcuffs under more normal means. Force is only justified when force is being faced. Officers should never surrender safety tactics, but “officer safety” cannot cover excessive and illegal use of force.

The age, size, and any disability of the suspect will weigh heavily on the opinion of the court when determining if any force used was justified or not. As will the age and size of the officer, in comparison to the suspect. The Courts have been paying particular attention to the use of force against mentally ill subjects recently, and that disability will definitely be viewed in special light by the courts when force is used against the mentally ill.

A Personal Example:

When I was a new patrol Sergeant I assisted officers investigating a juvenile out of control. During the investigation it was determined that the 15-year old had assaulted family members and needed to be taken to a mental health facility. However, when we went to take him into custody the fight was on. Normally, the use of force justifiable against a teenager would be rather limited. This “young” man was a wrestler in high school and weighed nearly 200 pounds. Obviously in that case we were justified in using greater force to overcome the juvenile’s resistance to arrest.

In that particular event it took four officers, about 10 minutes to finally get the juvenile under control. We had to use hand and foot strikes, the Taser, joint locks, and LVNR, and brute force to get him secured into handcuffs, and more force to get him into the back of a patrol car. Interestingly, the juvenile’s family cheered us on from the couch as they continued to watch Jeopardy. The truth is stranger than fiction! In that case, the larger amount of force was necessary to accomplish legitimate needs.

The point is, a fleeing suspect does not justify the uncontrolled unleashing of force against them. Age, size, and mental capacity of the suspect will be considered just as much as the alleged crime, and how much resistance was offered to arrest. Officers are bound by an oath to follow the U.S. Constitution and uphold the rights of all – even the very suspects that have fled or resisted arrest.

Police use of force will be viewed under the 1989 Graham v. Connor decision, in light of whether the actions were “objectively reasonable”. Continuing to beat a handcuffed suspect, or suspect who no longer resists, will not be justified, and will likely move the law enforcer into the status of defendant.

The BlueSheepDog Crew wants all of our law enforcement readers to be safe as they carry out their duties, but we also want them to work smart. A true professional removes the emotion of the event, and can take care of business with appropriate use of tactics in a manner that remains lawful. The officer must be able to rise to the highest level of force (deadly), and shortly thereafter be able to come down and offer medical assistance to the very person that the deadly force was applied.

The ability to master emotions, and successfully navigate the use of force continuum, is the mark of a true law enforcement professional.