The information presented in this article is for discussion purposes only. It is not legal advice no actions should be taken based on it. You should consult with your department’s legal counsel for guidance.

The department policy manual is a good guide to doing your job. The manual is an excellent reference for topics such as the proper way to dispose of found property, where to place your ribbons on your Class-A uniform, or how to file a grievance. However, when a lawsuit conscious administrator starts typing the policies, the manual can hinder more than it can help. Take the ‘use of force’ policy.

A lot, if not most, police departments lay out a use of force continuum that is linear in nature. Along the line are subject actions and appropriate police responses. Most policies allow a police officer to move up and down the scale depending on the circumstances, with the admonition that officers are to “…use the minimum amount of force necessary…” Sounds good, but its not. Here’s why.

No one can possibly know what the “minimum amount of force necessary” in a given case could be, and this opens you and the department up to endless second guessing by a jury when the “poor victim of police brutality” takes you to court.

In the landmark case, Graham v. Connor (490 US 386 (1989)), the United States Supreme Court took notice of this fact, and simply required police officers to use a “reasonable” amount of force based upon the totality of the circumstances known to the officer. Additionally, the Supreme Court stated that officers should not be judged with “20/20 vision of hindsight.”

So, how does this play out in the real world? Let’s say you roll up on a EDP (emotionally disturbed person) who is running into traffic and screaming at cars. If you don’t do something quick, he may get hit and killed by a passing motorist, or he may cause a serious motor vehicle accident. He ignores your verbal commands, and when you try to escort him from the roadway, he actively pulls away from you and assumes a fighting stance.

What is the “least” amount of force: oleoresin capsicum (pepper) spray, a TASER, a baton, or a strike with your personal weapons (hands, feet, etc.)? The plaintiff’s attorney will present your department policy to the jury, and then present an expert who will say that there were other lesser force options that were ignored by you.

If your policy reflects Graham v. Connor, and you are simply required to be reasonable in your use of force, you may choose any of the above force options to control the situation. All you have to show in court is that your choice was a reasonable choice. It is a lot harder for an attorney to show that you were unreasonable.

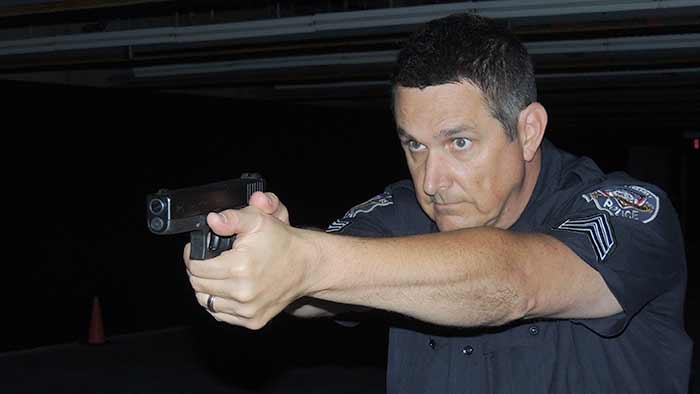

Here is another example. You respond to a local motel on a report of a shooting. When you arrive, you spot a person matching the description of the shooter walking away from the general area of the reported crime. You bail out of your squad, draw down, and order the person to put their hands up. The subject glances back at you, and instead of complying, he spins towards you while bringing his hand from the small of his back and starts to point something at you. Fearing for your life, you shoot the person. Unfortunately, you discover the subject is not the shooter, rather he is a deaf man who was trying to show you a plaque he carried indicating that he is deaf. Uh-oh.

If your department requires you to use the least amount of force necessary to control the situation, you have violated policy, as mere officer presence was enough to gain compliance from this person. On the other hand, the objective reasonableness standard accounts for the fact that you were using the best information you had at the time of the incident, and that when the subject, matching the description of a shooter from a nearby crime, made a motion consistant with drawing and pointing a firearm, placed you in reasonable fear of being shot.

I hope this makes sense. A lot of people would rather gouge out their eyes than read court opinions, but Graham v. Connor is one of those big ones every officer needs to read. Keep in mind that none of this is legal advice, nor am I suggesting you deviate from your department’s policy. Rather, if you have a policy more restrictive than the Supreme Court standard, you may want to pursue a policy change. Contact your department’s legal advisor and/or union lawyers/reps, and work to improve the policy you are held to.

Stay safe!

Update

In the 8+ years that have passed since this article was written, a lot of things have changed. Not in the courts, but in the public consciousness. Unfortunately, a lot of public sentiment is now against law enforcement officers. Aaron takes a look at some of the suggested guidelines from the Police Executive Research Forum here.

Leave a Reply