In 1989, I found myself staring down the throat of Hurricane Hugo, a Category 4 hurricane which frequently gusted up to Category 5 status. My career had spanned a broad range of law enforcement experiences, but I quickly discovered how naïve I really was. The lessons learned didn’t come easy, but they proved invaluable in 1992 when I was dispatched to assist the Homestead (FL) Police Department in the aftermath of Hurricane Andrew.

As is typical of most law enforcement organizations, our members had completed a wide variety of training programs considered adequate for preparing for natural disasters. Once the location of Hugo’s projected landfall became evident, the Charleston County (SC) Police Department hastily executed additional training, planning and preparation. But, those of us who experienced the reality of this monster storm will assure you that nothing could have prepared us for what was to come.

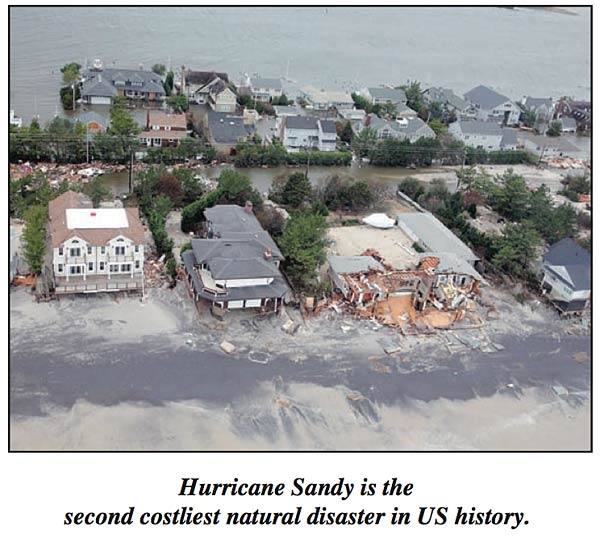

Hurricane Hugo was far more intense than Superstorm Sandy, the storm which ravaged the Northeastern United States this past October. But, Sandy left behind a trail of death and destruction exceeding that of Hugo, making it the second costliest natural disaster in U.S. history.

Problems and Solutions

This article is not a critique of public safety’s response to Sandy or any specific natural disaster – and it is not a rehash of the stories we’ve all followed in the national media. But, rather, it’s a small sampling of the types of problems law enforcement personnel typically encounter when responding to catastrophic events.

Law enforcement officers and citizens alike share similar emotions before tragedy strikes. When forewarned, we initially experience nervous excitement and anticipation, and even delude ourselves with denial (“It couldn’t happen to me.”). Postevent photographs of destroyed homes and buildings with boarded up windows suggest that many of us think we can mitigate disaster with simple preventative measures. But, such notions are quickly dashed when we see the indiscriminate destruction of familiar buildings and cherished landmarks. When the disaster abates, the reality of widespread destruction quickly leads to denial, anger and even despair. Public safety personnel must be prepared to focus on serving their public while putting their own needs on hold. In my own experience, I worked to help others find shelter, food and water while my wife stood and watched Hugo’s torrential rain pour through gaping holes in our ceiling.

Let’s Get Personal

Realistically, some officers/employees will ask to be excused from duty in order to handle their personal problems. If the request is denied, they may simply refuse to report for work. Do you respond with compassion or discipline? Remember, your response will establish precedence and others will expect to receive the same treatment.

Does your organization have a pool of qualified replacements to fill the vacancies which typically occur? If so, will the backups have to assume the added burden in addition to their own responsibilities? If your only recourse is to compensate by increasing the workload of faithful employees, you should expect employee frustration, anger and fatigue. And, you can anticipate requests for “extra duty pay”!

The demands encountered in postevent recovery are far greater than those experienced during normal routine. But, allowing officers to work beyond normal limits is dangerous and, potentially, illegal. Exhausted officers are already dealing with a variety of negative emotions and 12 to 14 hour shifts (for extended periods) will hamper morale, efficiency and good judgment.

The importance of hygiene and grooming cannot be overemphasized. Officers need the time (and facilities) to meet these needs. If you don’t have functional organizational facilities where officers can clean up before (or after) the shift, consider making temporary arrangements, such as portable or leased facilities which were not damaged by the disaster. Similarly, you should have arrangements in place to ensure an adequate supply of laundered uniforms.

Employees who are detailed to command posts and operations centers are typically “marooned” until the catastrophic event abates. If the parent organization does not stock food and water for these employees, individuals should plan to report for duty with enough provisions to last for the duration. And, since recovery can be a prolonged process, consider making advanced arrangements with generous organizations, such as the Salvation Army, for mobile food canteens at centralized locations.

As public safety officers know too well, law enforcement can be a thankless calling. But, officers should be prepared to encounter a wide range of emotions in dealing with the public. Citizens who are in a crisis mode may not understand that officers have to concern themselves with the “bigger picture,” focusing on the greater need. Ironically, troubled citizens sometimes see public safety personnel as being part of the problem, rather than part of the solution.

The Buck Stopped Where?

The handling of “nonessential” administrative and support personnel can be complicated. Do you expect them to report to their normal workstations, or perhaps use them to augment joint response centers? If they’re unable to perform their usual duties, can public works use them to pump gas or perform other necessary duties? Is administrative leave a logical and appropriate solution, especially for those who can’t get to work? Remember, people are more dependent upon their incomes for survival in the aftermath of any major disaster and the withholding of pay is certain to have serious repercussions. This is especially true when the disaster has long-term implications and the recovery process stretches into weeks and months.

Any strategy which pays employees who did not (or could not) work will generate problems and you may have to consider additional compensation to those who actually did work (i.e., comp time or special bonus pay). Incidentally, employees who are paid for staying home during a major disaster will have little or no incentive to work during a subsequent crisis. As a result, you may find that some employees will simply stay home during the next catastrophic event.

Problems with employees who are “exempt” from overtime compensation are a virtual certainty. This is especially likely if there are exceptions to class distinctions. For example, an exempt lieutenant who is assigned to duties identical to those of a nonexempt lieutenant (i.e., in a command post or operations center) is likely to question the fairness of compensation policies. You might mitigate this problem by arranging with your governing authority to waive exempt classifications during times of emergency. But, remember, any decision to waive classifications or award special compensation will generate controversy. Complaints of preferential treatment and discrimination can be expected from those who fail to see the “big picture” or understand command strategies and tactics.

Because increased overtime is inevitable, departments must have policies and procedures in place to properly manage the expense. Overtime work should be legitimate and, when possible, must be subject to command approval. Supervisors should also be prepared to monitor the accuracy (and veracity) of time sheets and must be thoroughly familiar with federal law as it relates to compensation. Failure to comply will result in lost pay and even charges of impropriety.

Officers, by nature, prefer to be “in the field.” But, a failure to meet their (dreaded) administrative responsibilities can adversely affect their welfare and morale. Attempts to “reverse engineer” incident reports, time sheets and other documents after the fact is both difficult and inaccurate. It can also jeopardize the awarding of state and federal grants, while subjecting the organization to accusations of fraud, waste and abuse. Expect grant approving authorities and postevent auditors to conduct thorough reviews of procedures and submissions, as well as compliance with laws, rules and regulations. Experience shows that it literally pays to be thorough, accurate and timely.

Many officers use their own citizens band radios, cell phones, laptops, tablets and other equipment in their cruisers. Does departmental approval for the use of personal equipment incur a replacement liability for your organization? You should establish liability policies addressing the use of personal equipment, since these items are normally not reimbursable by grants or government insurance policies.

It’s Not Your Daddy’s Department…

Expect status quo to evaporate during the response phase. A mind-set of “that’s not the way we used to do it,” or “we’ve always done it this way,” is the legacy of a forgone reality. A catastrophic event is likely to impose permanent change upon your organization – expect a significant paradigm shift. Necessity will quickly reveal which policies and procedures are coherent, logical and worth keeping. But, those which are outdated and irrelevant will become apparent as well. As your response evolves, understand that many of your actions will become de facto precedence for permanent changes to policies, plans and procedures.

There is no better example of this than the radical changes initiated by the 911 terrorist attacks.

How much flexibility will your organization afford its officers in times of crisis? If communications are disrupted, will they be empowered to handle situations beyond the scope of their training, past experiences and rules of conduct? How much discretion can they use in enforcing the spirit of the law as opposed to the letter of the law? If an officer is confronted with a crime in progress while responding to an accident or injury, is he allowed to determine what’s in the best interest of public safety? Conversely, does the organization have suitable means for preventing officers from abusing authority in times of crisis, such as the use of dash cams or other means for subsequent review and investigation?

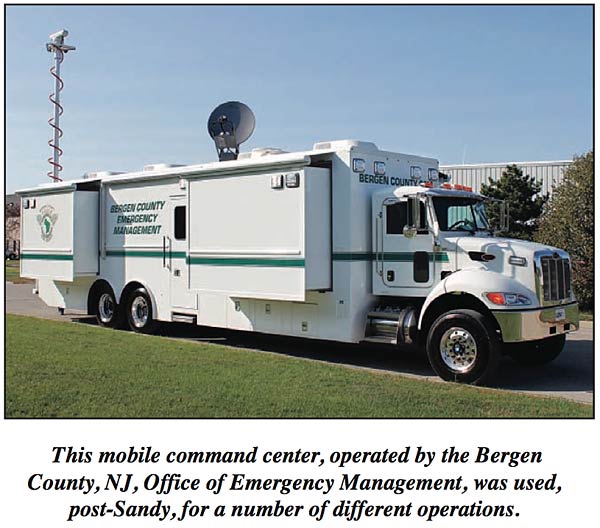

How much of your organizational functionality relies on technology? Can your organization still meet its mission objectives if mobile laptops are rendered useless, cell phone towers are destroyed and phones no longer work? Do you have a mobile command post which can handle telecommunications if central dispatch is somehow rendered inoperative? Do your officers and employees possess the fundamental skills and the rudimentary equipment needed to do their job if facilities are destroyed or equipment fails catastrophically?

You should expect to encounter unconventional problems such as price gouging. Outsiders often see the potential for personal gain in natural disasters and “seize the day!” They show up with bottled water, food, generators, chain saws and anything else for which the demand is great, but the supply is small. They can enrage their potential customers by charging outrageous prices for basic commodities. Other unusual problems encountered might include looting, vigilante committees, phony officials and other impostors, a serious degradation of infrastructure, etc.

Supplies and Demand

Your organization should have sufficient quantities of supplies on hand. You do not want to run out of flashlight batteries, or other essential supplies, early into the response and recovery phase. Are your stores fresh and functional, or are they stale and unusable? Has technology made them obsolete? You may discover that your five-year-old cache of laptop batteries is not suitable for your current models, or has simply become worthless due to age. Generators and emergency equipment should be tested regularly and you should have sufficient fuel reserves. If not, consider making prior arrangements to have fuel delivered on a timely basis.

Are you prepared to handle arrestees in the aftermath of a catastrophic event (e.g., looting, violence, etc.)? How will you transport them if your vehicles are deployed, or have been damaged by the disaster and rendered useless? Are the magistrates and other courts capable of processing arrestees? If not, how do you plan to dispose of them? Are your holding and detention facilities functional and adequate?

You should expect intergovernmental conflict, especially when public safety is given priority access to gasoline, food, water and other necessary supplies. Conflict is inevitable as other departments assert their needs, demanding equal access to limited resources. Caution is strongly recommended in resolving such disputes because of the long-term problems which can plague organizations well after response and recovery has been completed.

A Better Tomorrow

Law enforcement is unpredictable by nature and officers live in the moment as they oscillate between tedium and terror. Competing demands of mission objectives, departmental initiatives, public needs and budget restrictions tend to inhibit long-term considerations and planning. But, serious consideration should be given to deploying key personnel to other jurisdictions during, or immediately after, catastrophic events. Careful scrutiny of post-event critiques from other jurisdictions will also help you prepare for future disasters in your own jurisdiction.

Key staff members should become thoroughly familiar with the potential sources of grants and other forms of aid. Implementing proactive measures before the disaster strikes simplifies the application process and promotes approval. You may not expect to be ravaged by a hurricane, but earthquakes, fires or tornadoes may pose a serious threat and you should plan accordingly. Ensure your plans are current and realistic and do not hearken back to a bygone era. If you can accept the fact that surprises are inevitable and nurture an organizational culture of flexibility, your overall strategy is less likely to be jeopardized when the unexpected is encountered. And, remember, “This too shall pass!” Stay focused on the certainty that you will prevail over the circumstances, and assure others that they can anticipate a better tomorrow.

About the Author: Dr. McClinton retired as a special agent and intelligence officer in 1989. He then worked for the Charleston County Sheriff’s Office for 14 years and served as the Chief Deputy Clerk of Court in Berkeley County, South Carolina, for four years. He retired from the College of Charleston in 2011, where he served as the Direc- tor of Finance and Planning for Information Technology. McClinton graduated summa cum laude with a BA in Public Administration. He’s also earned an MA in Humanities and a Doctor of Philosophy in Management.