There have been tremendous advances in flashlight technology over that last decade, and law enforcement has greatly benefited from the many new features that can be found on relatively inexpensive flashlights. Along with those advances have come new techniques for using an indispensable tool.

Advances in LED technology have allowed manufacturers like Streamlight, Surefire, and Elzetta to make small flashlights with incredibly bright beams. These new lights are compact: usually only 4″-5″ long and about 1″ in diameter: no bigger than the average person’s palm.

Instead of heavy D-cell batteries, modern duty flashlights often use AA and CR123 batteries for lighter weight. Additionally, modern lights frequently use a thumb-activated on/off switch on the tail cap that can be a tactical advantage in many situations.

With the advancements we’ve seen in LED technology, manufactures have added different light settings including high output, low output, and even strobe and dimming functions on lights.

In this article I hope to explore some of the benefits of the smaller tactical flashlights, and combine that with some low-light techniques with which every patrol officer should be familiar to ensure success.

Using Light Full Time

There are times when having your flashlight on continuously is a benefit to the officer. Here are a few examples:

- Interviewing subjects on stops or calls . It allows officers to keep a clear view of the subjects hands and movements, while offering a distraction (by shining the light in the subject’s eyes) should the person become combative.

- Writing citations or notes in the field.

- Searching for evidence or missing persons.

- Directing traffic at crash scenes.

Another great time to keep light on full-time is once a suspect has been located during a search. At that point, we need to use the light to its fullest ability to hamper our suspect’s ability to see us or adjust to the rapid changes from dark to light. Plus we want to see every movement that our suspect makes to identify signs of fight or flight.

Full-time light in this situation can have a paralyzing effect on people who are surrounded by darkness. Humans rely heavily on eyesight for external stimulus and information, so taking away a suspect’s eyes with full light is a very beneficial thing. Full-time light also provides us with our best sight picture in the event of a deadly force or other applied force situation.

When using light full-time officers should be keenly aware of using the light to its greatest advantage. What I mean is that the light should be used to blind the suspect or illuminate the suspect’s hands. Hands kill us so we have to know what they are doing or holding. Once we have established that the hands are empty than the officer should use the light to eliminate the suspect’s ability to see, and therefore eliminate their ability to develop an organized plan of attack, resistance, or escape.

Potential Disadvantages

Some officers have advocated turning all lights on during an interior check, and although there are some benefits to this method, there are also times where it leaves us at a disadvantage.

For instance, if you turn a light on in a living room you are completely illuminated, but a suspect in the darkened adjacent kitchen or hallway may not be visible. In addition, officers have to cross completely lit territory in order to continue clearing the areas of uncertainty.

A good home defense technique is to leave a hallway light on so if an intruder enters your darkened room you have the advantage of concealment while they are completely backlit. The same thing applies to officers and can be used against us.

Officers that train and practice operating in the dark, can actually become quite comfortable being in the dark or semi-lit conditions. In these training scenarios, the darkness becomes our friend, and we are able to use it for our advantage.

Painting with Light

Another way of using full-time light to our advantage is the method of “painting” the light. Instead of simply pointing the light in one general direction, think about painting a wall. There is a lot of up/down and side to side movement, and probably some diagonal movement too so that the whole wall is covered and there are no obvious signs of brush strokes. This same movement can be used in the full-time lighting method to confuse suspects.

Try keeping your flashlight on and then moving your flashlight in rapid and different directions. Nothing extreme, in fact shorter and more controlled movements are better, but changing the patterns continuously. This gives a great amount of light for the officer to examine their surroundings but is very confusing to the suspect because it does not allow them the ability to determine how far away you are with your light. In some situations it will even confuse the suspect from knowing where the light is coming from, because light will be hitting all the walls, ceiling and angles, creating confusing shadows and light patterns.

Try this with your fellow officers. Have them hide in a darkened room or down a hallway. Use the method as described above and ask them how well they could determine where you were. They might have a general sense of where you are coming from but not an exact distance. This is great in a hallway where a suspect may be hiding around the corner.

Using this method and being quiet may allow you to move in the hallway without the give-away signs of how close you are getting that happens by leaving your light on and pointed in one position down the hall. Noise discipline is important here too, because the more stimulus you give out the easier it is for the suspect to start triangulating position.

Intermittent Use of Light

The intermittent use of light is one of the most advantageous methods of flashlight use for law enforcement, but also one of the most misunderstood, and therefore misused, methods. With this technique, officers should only be turning their flashlights on for a brief lighting, or making rapid on/off switches of their flashlight. Here are some examples where intermittent light is needed:

- Initial lighting for areas of concern to the officer.

- Lighting an area that the officer is preparing to move into.

- Communicating to other officers areas they should focus on, or to communicate the direction of travel for officers.

- Relighting an area after making a movement in total darkness.

- Making quick peek observations into unknown areas.

- Engaging a hostage taker during an emergency action movement.

Obviously lights with a strobe function can simply be turned on to strobe for brief times to illuminate areas of need. Otherwise, officers should turn the light off when they feel that area is reasonably clear, to provide themselves with the concealment of darkness.

This on/off method of light use acts to confuse the suspect as to what our intentions are and where we might be going. In general people have trouble gauging time and distance without light.

An on/off use of the light increases the confusion for the suspect because it makes it nearly impossible to accurately judge where an officer is or where they are going.

Officers need to train and practice extensively to be comfortable in the dark. There is a reason that our military troops have been so successful around the globe – we rule the dark through night vision optics and proper illumination techniques! Talk to veterans of the special forces community and I’ll bet many will tell you they’d rather fight at night than in daylight. Many high risk duties occur at night so we should be that comfortable as well.

The brain is a remarkable instrument if trained properly. You should practice moving through dark houses, buildings and yards with very little use of light. An officer could easily gain the skills to observe a room or area with only a few momentary bursts of light, and then actually move through that room or area relatively safely in darkness.

Imagine the suspect’s surprise as they try to track the officer’s movement, see the light in one area or room, and then only moments later the light appears (briefly) in an entirely new area.

Now to be sure, this technique is best used when we are in search mode and have to go through open areas that do not offer much cover.

I understand that in search mode our mindset must always be thinking that there IS a suspect hiding somewhere in the area we are going, whether in that room or the next, so we must move as stealthily as possible.

Maintaining noise discipline is just as important as light discipline during these movements.

If contact is made, or something peeks the officers interest, than another intermittent light use should be employed to examine that area of concern. If a suspect is located, than we switch to full-time light as mentioned above. In a situation where an officer was on the move, it would be necessary for the officer to maintain full- time light on the suspect, while continuing to move to a position of cover.

Through dozens of force-on-force scenarios (often with SWAT officers as bad guys) I can tell you that proper use of intermittent lighting causes the “suspects” to be very concerned that the pain train is coming unless they surrender!

I have had the luxury of training with officers and instructors that have hundreds of hours of low-light techniques training and experience, and I can attest that the confidence to perform well in darkness can be achieved fairly quickly if practiced correctly. And when you use the proper techniques the effects are devastating for those who wait in hiding to do you harm, or who simply try to stay hidden.

The Quick Peek

Another good example of intermittent light is when officers perform a “quick peek”. The quick peek is done when an officer is in a position of cover, behind a wall or at a door frame for example, and the officer wants to examine where they are going without exposing themselves for long.

A quick peek in most cases will be performed after the officer has “cut the pie”. “Cutting the pie” is a technique where officers slowly and deliberately move around corners to examine the area past that corner – most commonly at doorways, or the ends of hallways.

In the quick peek method an officer holds at the position of cover, and first uses their other senses. Yeah, use of flashlights is great but don’t forget the other senses while doing so. If you are at that position of cover and smell a cigarette, or body odor, or hear noise then stay behind cover and call the bad guy out to you on your terms! If you don’t have any other sensual stimulus but you still want to confirm that the area you are going into is relatively safe use the quick peek.

To do this, the officer must concentrate on what they are doing to get the timing right. When the officer is ready they will move in darkness to a point where their light, gun, and eyes can see where they want to look. This should only expose the bare minimum of the officer’s body. As soon as the officer is in that position conduct a quick on/off of their flashlight in the direction that the officer wants to see. Once done immediately withdraw back to cover.

The goal of a “quick peek” is to allow the officer to see into a threat area, but not long enough to give a suspect time to fire or attack the officer. The officer is taking a snap-shot picture of what he saw, and allowing that picture to develop while in cover like an old Polaroid instant picture did (younger officers Google it!).

If the officer needs to look in the other direction into the hot area, than they need to make sure they displace and conduct their “quick peek” from a different position (kneeling, modified prone, etc.). The quick peek should be performed from start to finish in about one second, less for those who are highly practiced in the technique.

Depending on the circumstances, the officer can follow with “painting” the room or moving on to another area, hopefully under the concealment of darkness. Something officers should remember is that all of these techniques are tools for the officers. Officers should not feel compelled or bound to follow a certain set of rules on using their flashlight, but instead take all of these techniques into the field and use the ones that are appropriate for the situation they find themselves in.

With all the good that the on/off or intermittent use of light brings, this area of light use also brings with it a certain mystique and plenty of naysayers. I firmly believe that those who aren’t fans have either never tried it, or more likely, have tried it incorrectly and quickly discarded the technique because of early failures. To be certain, this method of light use requires the highest level of training and practice, otherwise it will lose its powerful and positive effect.

An example of a failure to properly use intermittent light would be an officer who simply flashes some light in a certain area but doesn’t take mental photographs of what they are seeing. In that case the officer has simply wasted time and effort. An officer must train themselves to know that they are going to briefly turn the light on, and train the brain to respond to the limited stimulus by recording information. It is very possible! You’ll be amazed at the amount of detail and information you can gather from a flash of light that is on less than one second.

Quick Peek Experiment

Have an officer stand in the deep corner of a room (the corner that is adjacent to the doorway) and make the room as dark as possible. That officer will do something particular for the lighting officer to identify (make a peace symbol, be sitting with hands up, have hands in a position to shoot, etc.). The officer with the light will move their head (eyes), flashlight, and training weapon into the room while still dark to do a quick peek. Start with no time limits so the movements can be mastered. Then as officers master the movements, start dialing it in with time restrictions – must be completed in 2 seconds, 1.5 seconds, 1 second.

After the officer has moved back to cover allow their brain to start developing that picture. Then ask the lighting officer what they saw in as much detail as possible. Once the lighting officer does well with one officer, try two or three, or have other types of objects or stimulus for them to identify. You’ll be amazed about how much information you can gather in such a short time.

One thing to remember is that action is always faster than reaction. Here, we are expecting that our action will be faster than the suspect’s reaction. This requires a combination of speed and skill. As you train this technique and start feeling more comfortable, step it up a notch. Get everyone in protective gear (full face masks, etc.) and give the “suspect” a Sims or Airsoft gun. Let the “suspect” know that they have a green light to shoot the officer whenever they have a chance. Then let the officers perform the same drills.

The successful officers will come away even more convinced of their abilities in darkness. If an officer is hit then review why they were hit – too long exposed, improper lighting, talking out loud to partners about what they’re going to do, or peeking from the same point repeatedly.

The quick peek has limitations. If done improperly the picture will not provide the officer enough information to make decisions. If the officer lights up before entering the room then they have telegraphed their movement and are susceptible to danger. If the officer lights up as they are leaving there won’t be enough information to process. And if the officer stays in the room too long they are open to danger.

This technique requires practice, practice, practice!

Another thing to remember is the rule of 3! This is an old war rule that says the first to light a cigarette gets the enemies attention. The second to light a cigarette zeroes the enemy onto location. And the third to light gets the bullet! Same goes here with lighting. If you need to do another quick peek DO NOT do it from the same position you just performed!

Displace to kneeling or even modified prone (if you’re really good at it) and look from a whole new area. Suspects believe you’re going to engage them from standing and can guesstimate where you will be coming through that door. You can light up from high while your head is low, or light up low while your head is high. Suspects are naturally attracted to the light so this technique should give even more protection for your noggin.

Darkness Techniques

There are times when remaining in near darkness is actually a great advantage to officers. Here are a few situations where being in near darkness is actually a benefit:

- Maintaining a perimeter position.

- Moving through open areas that offer little cover and are exposed to the suspect.

- Crossing fatal funnels.

- Moving through fatal funnels.

- Hiding from your supervisor … uh, wait, different article!

When on perimeter duty for trying to lock down a fleeing criminal it could definitely be advantageous to remain in near darkness and allow our sense of hearing or smell to assist us.

Standing around with a light on full-time may be beneficial if we are absolutely certain the perimeter was set up in time. In that case the light should lock the suspect down, or at least identify his flight path.

If we aren’t sure, or we’re dealing with a known armed suspect, then setting up a perimeter in darkness may be more appropriate.

Whether inside a structure or in an open field, movement across open areas is of particular concern to officers. In most situations this movement should be completed with as little or no light as possible.

This would be a great opportunity to mix techniques. Officers could intermittently light up an area they want to cross for the purpose of identifying obvious trip hazards or other obstacles. Then, under the concealment of darkness, officers could move across that area in a reasonably safe manner. Again, noise discipline will be a critical concern in these situations as well.

Fatal Funnels

Crossing fatal funnels is a horrible reality that officers must face. A fatal funnel is any location that focuses the area a suspect can expect police movement. This could be a doorway, a window, a hallway, a pathway through woods, etc.

This obviously increases the chances that an officer will be attacked while in the funnel. Since this type of movement is frequent in police work, officers should investigate as many techniques as they can find on how to successfully navigate this threat area.

One of the things that an officer might be able to control is the amount of light available at the funnel. After using other lighting techniques to “quick peek” or “cut the pie” the officer can go “lights out” and rapidly move across the funnel under concealment of darkness.

“Cutting the pie” allows the officer to remain behind a position of cover while exposing the majority of the room for officer inspection. The final movement is to “quick peek” the deep corners before moving into the room. In this manner the entire room can be examined before crossing the threshold.

Communication

Communication with other officers is critical so they don’t back light an officer during this movement. “Lights out” should tell all other officers that a movement in darkness is about to occur, and they need to turn their lights off and be quiet. “Lights out” means lights out! In most circumstances, this instruction will come from the lead officer, but may come from a cover officer who senses a threat from an area different from the main objective.

Limited communication is just as important, it should not let the suspect know what the officers are doing. Loudly proclaiming “lights out so I can cross this doorway” defeats the aspect of surprise. Officers should be comfortable with limited and quiet communications that are brief and to the point.

Entering a Room

Another time that “lights out” should be considered is when officers are finally ready to move through the funnel and into a room.

From “painting” and “cutting the pie” officers should have a good idea of a clear movement path. Obviously with furniture in the room there are still possible areas that a suspect could hide. When ready officers can call for “lights out” and then move into the room under darkness. Once in the room, officers can relight flashlights using an intermittent light technique until the room is clear or a suspect is located, at which time a full-time lighting technique should be used.

Moving into a room should be a considered and deliberate movement. This is not a slow movement, but movement with a plan. Officers still want to clear the funnel as quickly as possible, as there might be ambient light that partially back lights them. To accomplish this officers should move into the room and immediately step away from the doorway a few steps. This clears them from the funnel and allows room for backing officers to enter the room as well. Once inside the room officers should turn lights on to clear any remaining threat areas (like behind furniture).

There are two basic methods for entering the room – crossing and button-hook. In the crossing method, an officer is on one side of the doorway (e.g. left), steps into the room, and then steps across to the other side of the doorway on the inside of the room (right). This is the most natural form of movement into the room that still clears the funnel.

In the button-hook method, an officer is on one side of the doorway (e.g. left), steps into the room and immediately spins back in the same direction (going left), in effect following the contour of the wall they were using as cover.

In either method the officer should take 2-3 steps into the room to clear room for other officers to enter. Going too far into the room will cut off the angle necessary for backing officers to provide additional firepower should an immediate threat be realized. In addition, the officer should move in a manner that places them 3-5 feet away from the wall. This creates a moving target for any suspect that is hiding in the deep corner. If the officer simply moves along the wall they only create a bigger target.

The obvious concerns for the officers are the deep corners and these should be checked first. The deep corners are the ones adjacent to the walls of the room or hallway the officers are in before entering. Using flashlight lighting techniques officers should be able to observe the far corners from a position of cover, but the deep corners are often difficult to observe even with a “quick peek” due to furniture or other obstacles.

Once in the room the officers should sweep their weapons inward until the entire room is covered, but not crossing over their partners area to avoid “lasering” each other. Continuing to move while clearing obstacles is a good idea as long as officers are aware of their muzzle and do not laser each other and communication between officers remains constant. Once the room has been thoroughly checked a pre-set communication should be given, such as “nothing seen” or “clear”.

Hostage Situations

Many agencies do not have the luxury of a full-time S.W.A.T. Team, or even a part-time team that can be assembled in a reasonable amount of time. This is especially true in more rural areas where agencies may be a part of a multi-jurisdictional team that requires even more time to assemble. Whether it is the initial patrol officers or a S.W.A.T. Team that is handling a hostage taker situation, each style of lighting can be utilized.

The intermittent use of light can be an extremely effective tool in the event that the hostage taker must be taken out. Obviously the best use of intermittent light would be if the hostage taker and hostage are in a darkened area.

If the hostage rescue has to be performed in a lighted area I would still recommend officers use light on the hostage taker’s eyes to further distract them from officers’ movements.

In a darkened hostage rescue action officers can decide on two methods to engage the hostage taker. These techniques are meant for the common situation where the hostage taker is behind the hostage and holding the hostage close to themselves.

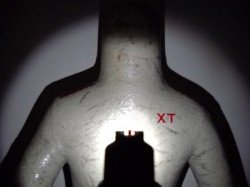

The point of these techniques is to get officers close enough to the hostage taker to allow officers to take a head shot on the hostage taker that affords the utmost certainty of avoiding the hostage.

In the first method some of the cover officers can continue to have full-time light on the hostage taker, while other officers move in the peripheral areas to a point where they can engage the hostage taker. The advantage of this is that there will be enough ambient light for the officers to move into position and see the hostage taker.

The disadvantages are that the hostage taker is not going to like the light on them, and the ambient light may expose the officers moving in and cause the hostage taker to take action against the hostage.

In the second method the officers maintain full-time light on the hostage taker until they have a reasonable plan of action decided. Then they can go “lights out” which has the appearance of doing what the hostage taker wants from them. Instead, with the hostage taker’s eyes now very much compromised to the dark, the officer(s) can stealthily but quickly take a flanking movement to the hostage taker’s position.

At the last possible moment the officer illuminates the hostage taker with a flashlight and takes as near of a contact head shot as possible to ensure ending the hostage taker’s threat, while avoiding injury to the hostage.

Now before any negotiators or administrators write any scathing responses about not trying to talk the hostage taker down I will restate the purpose of this article low light techniques.

Yes, officers should first try to negotiate or talk hostage takers into releasing their hostages and surrendering. But when the situation has obviously deteriorated and the officers have a reasonable belief that the hostage is in immediate danger of serious physical injury or death, than the officers must act.

In order to act effectively they need to practice techniques that will give them the best advantage. That is the only point of this article.

Final Thoughts

With disciplined practice, the techniques in this article will help officers to confidently tackle whatever scenario they face in darkness, and actually come to appreciate the benefits of darkness. I would highly recommend that officers review this material and perhaps practice some of the techniques, but seek out qualified training in the area of low-light engagements to fully appreciate the proper methods of using light.

Leave a Reply