It’s not a backup; it’s a last-ditch handgun!

There’s a significant difference between carrying a backup handgun and toting a “last-ditch” defensive arm. The North American Arms 22MS revolver chambered in .22 Winchester® Magnum Rimfire (.22WMR) fits in the latter category. While the NAA 22MS is suitable for concealed carry, its size, caliber and method of operation are not optimal for first line defense. For me, it’s almost too small to hold, let alone get a good firing grip; has to be cocked for each shot; and fires a rimfire round.

Conversely, its diminutive size means it can be hidden or concealed almost anywhere; there’s no safety to disengage; no magazine to pop loose; no slide to fail to cycle; and .22 Magnum rimfire ballistics are adequate, as it drives a 25- to 45-grain lead or jacketed hollow point bullet out of its 1 1/ 8″ barrel just shy of 1000 fps. This will certainly do more than give someone an “owie.” The NAA 22MS fits the criteria of a handgun which can be secreted somewhere on your person to be used only when you have nothing else left with which to defend yourself. At this point, you use it or lose it (both your gun and your life).

Historical Perspective

This most certainly is not a new concept, of course. I recall reading that General Douglas MacArthur carried a .41 rimfire Remington derringer, belying his otherwise unarmed appearance.

I also know of a local officer (now retired) who carried one of these in his spare handcuff case for many years. More recently and on a personal note, my wife was preparing for a formal evening affair which naturally indicated a very small purse. Wanting to be armed, she tucked away an NAA revolver in .22LR next to the other necessities in her purse.

I recall being exposed to this practice of carrying a “hide-out” gun back in the late 1950s. I confirmed my decision in the early 1960s. The first inspiration was, of all things, the TV western, “Paladin.” In it, actor Richard Boone (aka Paladin) hid a two shot derringer behind his singleaction Colt® pistol belt. In a number of instances, he put the derringer to good use when, after being apparently disarmed by a bad guy, he produced his concealed derringer and evened things up!

Then, in 1963, two Bakersfield lawmen were taken hostage by two armed thugs who killed one officer after one was disarmed at gunpoint and the other had surrendered his service revolver when the one perpetrator threatened to shoot his partner if this was not done. This incident became known as the “Onion Field Murder.” The following synopsis provides the general details of the tragedy:

“On March 9, 1963, at about 2200 hours, Los Angeles Police Department officers Ian Campbell and Karl Hettinger were conducting plainclothes patrol when they initiated a traffic stop on a maroon Ford coupe for an inoperative license plate light. The occupants, Gregory Powell and Jimmy Smith, were armed and looking for an easy target to rob. As Powell exited the Ford at Campbell’s request, Powell drew a gun, surprising Campbell and using him as a shield so that Hettinger could not shoot without hitting Campbell. At Campbell’s repeated request, Hettinger handed his revolver to Smith. With both officers disarmed, they were ordered to squeeze into the two-door Ford coupe with Smith and Powell and were driven to an onion field near Bakersfield, CA. Ordered out of the coupe, Campbell was shot and killed. Hettinger successfully escaped into the darkness, eventually finding a farmhouse, where the residents called for help at about 0100 hours.” The matter was memorialized by former LA police detective and noted crime author Joseph Wambaugh in his 1974 novel, titled The Onion Field Murder.

Don’t Leave Home Without It

From this tragedy, policies and procedures were developed and instituted covering car stops and officer safety, along with what to do or not to do if taken hostage. Unofficially (to the best of my knowledge), lawmen looked at this incident and saw the wisdom of carrying what was then termed a “hold-out” or “stingy” gun – a gun of last resort, if you will.

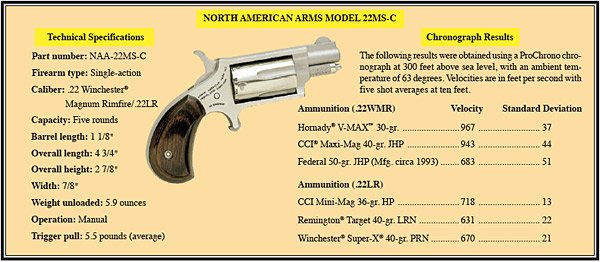

This is the niche for the North American Arms revolver and others of its ilk. The NAA 22MS, chambered in .22WMR as noted earlier, is a five shot, stainless steel single-action revolver with laminated rosewood grips; a blade front sight integral with the barrel; and a fixed rear sight notch. An optional .22LR chambered cylinder can be ordered for more economical shooting and one was provided for this review.

Another worthwhile item was also included –a LaserLyte laser which mounts on the top strap of the pistol. (The assembly was challenging, though, as “tiny” only begins to describe its assembly screws!) Several more nice accessories were sent: optional imitation stag and pearl grips; a boot grip which changes the round grip to a square and longer grip; pocket and belt holsters by DeSantis Gunhide®; and a lockable, soft carrying pouch.

How to Load and Carry

To load or unload the NAA revolver, the hammer is drawn to the first or half cock notch. Then, very carefully, press in on the front or forward part of what appears to be an extractor rod. When the face of the rod (actually a plunger) is depressed and held in, the rod can be drawn forward from the frame and the cylinder removed. It comes out easier to the right side of the frame because there’s a cylinder stop located in the left inside rear of the frame. Use the cylinder rod to remove the empty cases, recharge the chambers and reverse the unloading action while keeping your fingers away from the gun muzzle.

In real use and to the good, all NAA revolvers can be safely carried fully loaded if the hammer is lowered into the cylinder safety slots which are halfway between the cylinder locking notches.

Performing this action takes practice with an unloaded gun. The revolver must never be carried in the half-cocked position, as the purpose of this midway cocking position is to prevent the gun from firing if the hammer slips out from beneath your finger when cocking the pistol.

Results from the Range

Range work showed it’s easy to make effective torso and head hits at a one or two arm’s length distance. With the laser attached and on, hits were made (or not) based on how steady the gun was held while pulling the 5.5 pound trigger of the 5.9 ounce gun (unloaded weight). Without the laser, one-handed shooting at five yards gave us four inch to six inch five shot groups.

The .22LR conversion cylinder was an easy switch (simply follow the directions in the instruction manual). I found the cylinder easier to remove and install if done from the right side of the gun.

I shot an assortment of .22s, both .22LR and .22WMR, as indicated in the accompanying chronograph table. However, here’s an important note: In a supplemental sheet supplied with the sample and dated May 17, 2004, is the following warning: “… NAA has recently learned that the use of PMC .22 caliber ammunition (Magnum and LR) may affect the performance of its revolvers.

Specifically,NAA has become aware of a phenomenon where an inadvertent, double-discharge (two rounds simultaneously discharging, one aligned with the barrel and the other out of battery) may occur when PMC brand ammunition is used in NAA .22 revolvers…”

Realistic Shooting

At the range, Ted Murphy and I did more realistic shooting at point-blank to seven yards. The gun shoots where you point it and that’s all you can ask for. All of the NAA revolvers are “last-ditch” or absolute deep concealment handguns. We did find, however, that the alignment of the fixed sights needed adjustment, as the gun shot about six inches low at seven yards. Point shooting was more effective.

That said, this sample’s chambering of .22WMR or its sister version in .22LR should not be quickly dismissed as not adequate for the task. The chronograph results in the sidebar are encouraging as to the defensive effectiveness of this new group of .22WMR rounds, particularly when coupled with the new bullet designs. We did experience two misfires and two instances of a fired cartridge case head swelling to the extent that cocking the pistol for another shot was difficult. Since we had fired over 50 rounds at this point, I suspect both difficulties were due to our not firmly seating fresh cartridges in the now fouled charge holes. We had no such difficulties when, after a cylinder swap, we shot .22LR (but fewer rounds) and had similar accuracy results, but no misfires or swelling. The .22LR chronograph numbers are lower, of course, but they remain lethal.

The NAA .22 Magnum Rimfire Mini Revolver with 1 1/8″ barrel and conversion cylinder, the NAA 22MS-C, retails for $249; the LaserLyte laser is $109. The NAA Web site (see below) has further details as to adding the .22LR cylinder if you already own an NAA 22MS.

About the Author: Walt Rauch is a writer and lecturer in the firearms field. He is published regularly in many national and international publications and is the author of the self-defense book, REAL-WORLD SURVIVAL! What Has Worked For Me. Mr. Rauch has also authored, PRACTICALLY SPEAKING: AN ILLUSTRATED GUIDE to The Game, Guns and Gear of the International Defensive Pistol Association With Real-World Applications. To purchase a signed copy of Rauch’s books, phone (610)825-4245. Both books are also available at Amazon.com.

This article is a contribution from Police & Security News. P&SN is bi-monthly law enforcement magazine that is packed with training articles and gear reviews for the patrol officer. P&SN is a valued supporter of BlueSheepdog.