Ever heard the saying, “SPEED, SURPRISE AND VIOLENCE OF ACTION“?

If you’ve been in American law enforcement for more than a couple of years there’s a good chance you’ve heard this concept at least once. The terminology has been widely used within American law enforcement SWAT Teams for decades, and in some cases has spread out to patrol and other police units. However, the concept actually originated in the military.

Sounds cool, right? Well it sure is, most of the time! I have performed many missions under this philosophy and they have created some very memorable moments. However, law enforcement must be really cautious when mixing military actions, philosophies, and terminology with the civilian enforcement of the law. Don’t believe me? Read on!

EDITOR’S NOTE: This is Part I in a 3-part series discussing one of the most overused training philosophies among American law enforcement tactical teams. In this article, we will examine the first component of “SPEED”, and how it can be beneficial to officers, and how it can also overwhelm their ability to operate within the OODA Loop. This series is meant to shed light upon the dangers of using “Dynamic Entry” as the sole method of search warrant services or barricaded subject resolution and is in line with the National Tactical Officer’s Association (NTOA) recommendations and training.

Dissecting an Overused Police Tactic

This article may not sit well with some of my tactical officer brothers and sisters, but I’m willing to step out in the open to present an argument that should have been discussed years ago. The concept of “speed, surprise, and violence of action” is at the heart of dynamic entries. The two became almost synonymous and inseparable. Dynamic entries are typically associated with “no-knock” search warrants on locations known to house extremely dangerous offenders, or criminal activities (most often drug manufacturing and distribution and/or weapons offenses).

This type of warrant service became the standard tactic for many law enforcement tactical teams for decades but has actually been eroding in recent years. The National Tactical Officers Association (NTOA), the nation’s premier tactical officer organization, no longer supports the comprehensive tactic of “dynamic entry“. Instead, NTOA only recommends and supports dynamic entries on a hostage rescue or active shooter mission. Yet there are many law enforcement agencies that still perform dynamic entries as a matter of routine. Are we becoming our own worst enemies? In some cases, I think we are.

The concept of dynamic entry relies on police officers acting so quickly, and with surprise, that the suspects are unable to overcome their OODA Loop disruption, allowing the officers to succeed in their mission.

OODA Loop and Dynamic Entries

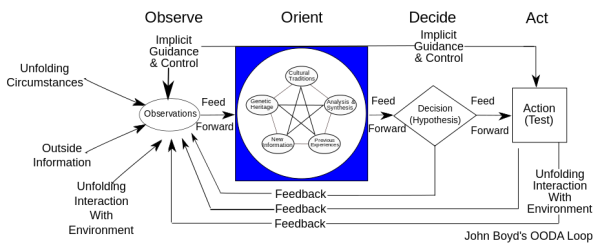

The OODA Loop refers to U.S. Air Force fighter ace and instructor Colonel John Boyd’s description of aerial combat and how to overcome and beat your adversary. The concept was so relative it has been incorporated by every military service and many in law enforcement as well. The premise is every person facing a threatening situation will cycle through a 4-step process before being able to act or react to the perceived threat. The 4-step process is:

- Observation

- Orientation

- Decision

- Action.

The key to Col. Boyd’s OODA Loop is to train and practice in such a proficient manner that you can cycle through the process faster than your adversary, even if the adversary starts the action. Being able to cycle through the process faster, can actually completely change the roles in the engagement – from you being surprised or threatened to your adversary facing those compromising dilemmas.

In tactical team operations, the goal is to act so overwhelmingly (speed) that we create a sensory overload (surprise) on the suspects, to the point that they get stuck on “observation” and cannot cycle through the process to act against us. In theory, this makes perfect sense, and when everything plays out the way police want them to, the results can be very dramatic and a powerful reinforcer of the tactical practice.

However, when facing the most dangerous suspects, who themselves have had to learn to quickly cycle through the process, our “dynamic entries” have a much shorter-lived effect. Suspects mentally prepared to resist have established barriers to such entries, and being on their home turf, can quickly turn the tables on SWAT team members.

Officers are entering an unfamiliar area, with potentially serious barriers, and are now required (practically and legally) to actually go backward in the OODA Loop to the beginning – Observation. Yet, they charge ahead at expected “dynamic” entry speeds, stuck in “action” mode. It’s not too hard to understand then, how non-threatening occupants get shot, or officers get shot. The officers over-extend themselves, physically and mentally, and enter a kill zone of a now well-prepared adversary.

The adversary has processed the information on familiar turf and already made the “decision” to act. The suspect simply waits for the stimulus of an officer entering their sights. The officers are legally required to observe their suspects, make a determination if they are a lethal threat, and then engage (act) with deadly force. This places the officers squarely inside the suspect’s OODA Loop, and woefully in the precarious situation of having to react to the action of a committed adversary.

A Close Examination

So let us examine this tactic or philosophy of “speed, surprise, and violence of action” more closely. This series will break down each component, explain its intent and purpose, and discuss ways law enforcement can ensure that we are keeping ourselves squarely separated from military actions, while taking advantage of methods and tools that legitimately make our jobs safer and more proficient. For the context of this discussion, I will be using structural or room entries as the basis of thought, since those actions are at the root of this philosophy for SWAT teams.

SPEED – Speed can be very beneficial, or it can be catastrophic. Getting to a hot call fast is great, while crashing along the way is horrible. The same applies to this tactical doctrine.

THE GOOD – Speed is beneficial when officers can move in a manner that allows them to overcome the suspect’s ability to orient themselves to the movement, process and understand what is going on, or take a well-aimed shot if they were already prepared to shoot. The old adage of “action is quicker than reaction” applies very well here.

When it comes time to enter a structure or a room, it is absolutely correct to move with a purpose. Cross the threshold, get out of the fatal funnel, stay off the walls, and scan with your weapon until you and your partner have dealt with any threats or confirmed that the room is clear. All of this should be accomplished quickly; in a few short seconds in most rooms.

The point of the quick (“dynamic”) movement is to get out of the most obvious kill zone available to any suspects inside. Once inside the structure, or room and beyond the threshold; however, officers should slow down just a bit to allow their eyes and mind to properly assess what they are observing and respond appropriately (and legally). Most professional firearms instructors teach, “don’t move faster than you can accurately shoot your weapon!” This concept is particularly important for tactical team members who are often moving during a mission.

When moving further into a structure, officers should actually plan their movements with the real-time intelligence they now have of the structure. Unfortunately, many tactical teams just rush, rush, rush – in a misguided belief their speed will still be too overwhelming to remaining suspects. Once the pedal is pressed, there’s no let-off until completion (or tragedy). Officers must understand further travel into a structure, the situation becomes more dangerous, not less. Any suspects in those deep, rooms have had more time to orient to officer movements, more time to barricade, more time to arm, and more time to plan their attack on the officers.

It borders on recklessness, and a breach of duty to the lives of the officers, for team leaders or supervisors to allow a “dynamic entry” tactic to continue beyond the first few rooms of a structure. Think about it, after the entryway and maybe living room of a typical house, what do officers start to confront? Hallways leading to bedrooms, stairs going upstairs or downstairs, all of which are fatal funnels waiting to bind officers into a tight kill zone.

The Priority of Life clearly establishes that officers are higher than criminal suspects:

- Hostages/Victims

- Innocent By-standers

- Officers/First Responders

- Suspects/Subjects.

Tactically sound doctrine would dictate slowing down, using shields or other cover at the entrance to these kill zones, and then calling-out any suspects. Some may say, “yeah and their goes the dope!” I say, OK! Better to send our friends home alive than chase dope to their deaths. Remember, officers are #3, suspects are #4 on the Priority of Life scale – dope doesn’t even make the list, or is at least below even the suspects!

THE BAD – Speed can be just as detrimental to the officers as it is beneficial. Lack of absolute intelligence on the structure’s layout, furniture, barriers, numbers of people and animals all play against the success of “dynamic entries”. Too many officers and tactical teams rush in thinking that speed will make them victorious.

Suspects are on their home turf. Multiple threat areas must be evaluated and decided upon before lethal force is used. The number of observations and decisions can are often overwhelming, slowing the ability for officers to make sound decisions.

This type of sensory overload on the officers plays right into the upper hand of the suspect who has a better vantage point and a much smaller threat area (usually the first entry point) to focus their deadly acts upon. Even on missions involving suspects known to be armed and dangerous, officers must satisfy legal requirements before using deadly force. To do this, officers can only move as fast as they can process information correctly.

The number of “no-knock” search warrants has been dramatically decreasing around the country, and are forbidden by law in some states (New Jersey for one). In my area they are not impossible, but are very rare. So when serving a search warrant the team must “knock and announce” our presence for a reasonable amount of time to give the occupants the ability to answer the door and submit. The Federal case of U.S. v. Banks established 15-20 seconds as a reasonable time for knocking and announcing officer presence and intention.

By announcing our presence for 12-15 seconds a team loses any reasonable consideration that “surprise” is still an element to be counted upon. So why in the world are we still using, “speed, surprise, and violence of action” tactics when the first element is completely gone from the beginning?

Dynamic Entry vs. Dynamic Movement

The NTOA has moved away from endorsing dynamic entries unless officers are performing hostage rescue or active shooter response. However, this does not mean the NTOA has stopped endorsing “dynamic movement”. There is an absolute difference between the two concepts. When making entry movements inside the structure, the concept is to properly evaluate the situation (threshold assessment and target identification) to determine the best course of action.

When enough information is known to the officer, and a decision to enter has been made, then the appropriate speed of that action is to clear the fatal funnel quickly. Once inside a room or open area, officers should slow their movement somewhat to allow themselves to accurately process their new observations. The overall movement through a structure should vary from speed to deliberate action, depending on the area, intelligence, and situation confronted.

This is why NTOA is now advocating an overall structure clearing technique of Deliberate Movement. This is not the slow and deliberate where movements are painstakingly slow. This is movement that clears an area but does not move so fast that the officer’s OODA Loop is over-taxed. This tactic recognizes there are areas to move very fast, and others where slowing down is the most appropriate.

This video shows a pretty good example of a Deliberate Entry. The team moves quickly into position and uses a flashbang after the door is breached. They then move through the fatal funnel quickly, but slow down once inside the room, properly engaging threats. They communicate the direction of travel, cut the pie at corners and doorways (which allowed them to see a deep threat in a room about midway through the video), and generally move at a fast walk. “Deliberate” is not slow, it is deliberate!

In short – Dynamic Entry should not be a “fix-all” solution to the way we do business. It should actually be used for only a very few extremely dangerous and pressing encounters.

Deadly Dynamic Entries

There have been dozens of examples where highly trained tactical teams or officers have rushed into a residence/room and suffered a devastating failure. They followed the concept of speed, surprise, and violence of action (something that had probably been successful for them 99% of the time) only to be confronted by a determined and prepared adversary who inflicted horrific casualties on the officers. These were not hostage rescues, these were not responses to active shooters, these were high-risk warrant services or barricaded subject calls.

WE MUST LEARN FROM OUR MISTAKES, AND LEAVE OUR EGOS IN THE LOCKER ROOM!

Phoenix SWAT Ambushed on Dynamic Entry

In 2013 Phoenix, Arizona SWAT conducted a no-knock search warrant on a known drug dealer in possession of illegal firearms (suspected fully automatic rifles). The warrant service was in the early morning hours, where speed, surprise, and violence of action is supposed to be at its greatest effect. The suspect’s door was barricaded and armored. Yet, the team forced entry (after a notable delay to remove the armored door) and began a dynamic entry.

The suspect had been asleep on a couch in the living room facing the front door, with a fully automatic rifle on his lap. The suspect fired at the entering officers, seriously injuring two team members before the team was able to retreat. The suspect ultimately surrendered peacefully when the team used surround and call-out procedures.

Once the element of surprise was lost at the armored front door, Team leadership should have quickly assessed the breach had failed and moved to contingency plans that should have been discussed and known beforehand. Considering the extremely dangerous characteristics of the suspect, a surround and call-out may have been the most appropriate mission execution decision in the first place. Once the breach failed, the officers should have immediately withdrawn to hardcover and used surround and call-out procedures. A secondary breach point really would not have been wise at that point because of the armed and violent nature of the suspect being faced – who now knows the team is there. Copious amounts of chemical agents could be used to alter the suspect’s willingness to remain barricaded inside.

Instead, the roller coaster was set in motion with only one option to solve the problem – the proverbial hammer. When the armored door was not easily opened, the team simply tried harder. They eventually succeed in getting the front door open, but all surprise was lost, and now the focus of all the residents was solely on the primary point of entry. Nobody on the team appeared to recognize the danger in continuing down the path they were going, which indicates to me that there really was only one plan of action – breach door, dynamic entry to victory!

Another clue of disaster was the entryway just inside the door. This suspect had prepared for a possible police entry or robbery. In addition to the armored front door, the suspect had placed heavy furniture at the entryway in a manner that funneled entry access into a very narrow pathway. This was a well thought out and executed ambush, and the SWAT team charged right into the kill zone.

This is why dynamic entry can be so devastatingly dangerous for police officers. Once the speed train leaves the station it is almost impossible to stop. Actions are preprogrammed to be fast – dynamic.

If everything goes as planned (or at least in favor of the officers) than everyone thinks this is a badass technique with outstanding results. However, if only a few obstacles get thrown into the mix, it is extremely difficult to recognize the dangers, abort the dynamic entry, and begin contingency action plans that are more appropriate considering the lost elements of speed and surprise. Instead, officers typically just move faster or harder when obstacles are confronted – as is the case with the armored front door in Phoenix.

Hostage Rescue and Dynamic Entry

If a hostage rescue must be performed, a dynamic entry is not only appropriate, it is what is morally and ethically expected of the officers. This is because the officers swore an oath to protect the innocent. The hostage is a victim, and their life is in peril.

The Priority of Life scale places the hostage, victim, or innocent bystander at the highest levels of importance, and above the officers as well. For officers to disregard standard safety protocols to rush to the aid of the hostage and stop an imminent murder, is at the highest calling and expectations a police officer has to perform.

I have heard too many officers express the sentiment, “it’s us against them”, or “police first, then everybody else”. These officers have no doubt been indoctrinated in a twisted “Blue Shield” mentality that completely forgets the oath of office.

It just goes to show how very difficult it is to remain on that thin blue line and uphold your oath and duties professionally. If those selfish mantras held true, those officers would never expose themselves to danger to protect victims or innocent bystanders.

The oath of office for a police officer necessarily places us at the service of others. It is true, that our neighbors have given us great authority to keep the peace, establish order, and even physically arrest them if they break the laws. However, they expect professional police officers to place themselves in harm’s way to protect them if criminals or nature are bent on harming them.

Could you imagine what the people of New York, and the world, would have thought about the police officers and firefighters on September 11th, 2001 if they had simply responded to the World Trade Towers and not gone in? Those men and women knew exactly what their oath meant, and tragically hundreds gave their lives to uphold it!

Final Thoughts

SPEED can be extremely beneficial in the accomplishment of police goals. There are definitely times when speed is appropriate and expected. Clearly, thresholds and other fatal funnels is a perfect example of when speed should be employed. However, just like in a high-speed pursuit, there are times when the officers must slow down in order to complete the mission at hand safely.

In the high-speed pursuit example, an officer who fails to recognize the need to slow for a dangerous curve in the roadway, or a busy intersection, will likely crash and injure themselves or others. That failure to understand the dynamics of when to go fast and when to slow down is the arbiter of their failure.

SWAT Team Leaders, supervisors, and officers who fail to recognize and acknowledge when going fast is appropriate, and when slowing down is appropriate, are stuck on the accelerator. Like the high-speed pursuit, those officers are just waiting for the first unknown obstacle to completely wreck their plans. Their reckless decisions and actions are unnecessarily leading officers into situations resulting in injury and death to the officers involved.

Todd says

This lesson also came out of the War on Terror. The ‘don’t run to your death,’ lesson. Retired Lieutenant – 26 year LE career. My son just starting his career in Law Enforcement shared the term “Throttle Control.” The knowing when to throttle down, or throttle back is critical. I like that term. I believe understanding surprise, speed & violence of action, helps explain how even trained LE guys, can be dragged from Jeff Coopers condition yellow or orange into condition black (panic – wrong thing or no thing) by falling behind in OODA. And often it’s not merely one OODA loop, but many. The last OODA loop is the one defining winners from losers. LE guys need to go first before we get to this last loop. For it is where the bead gets drawn, and the trigger gets pulled. All of these fundamental principles of combat action beats reaction, time distance & cover, OODA, Cooper’s Color Codes, surprise speed & violence of action, relative superiority (momentum), & others are all interconnected and compenetrated.

If you don’t yet see the connections study the “game film,” and look harder. Stay safe my brothers.

Aaron says

Excellent observations and suggestions Todd. Thank you for your service, and God Speed to your son as he begins his!